x

Indian edtech after the hype: why we are looking again now

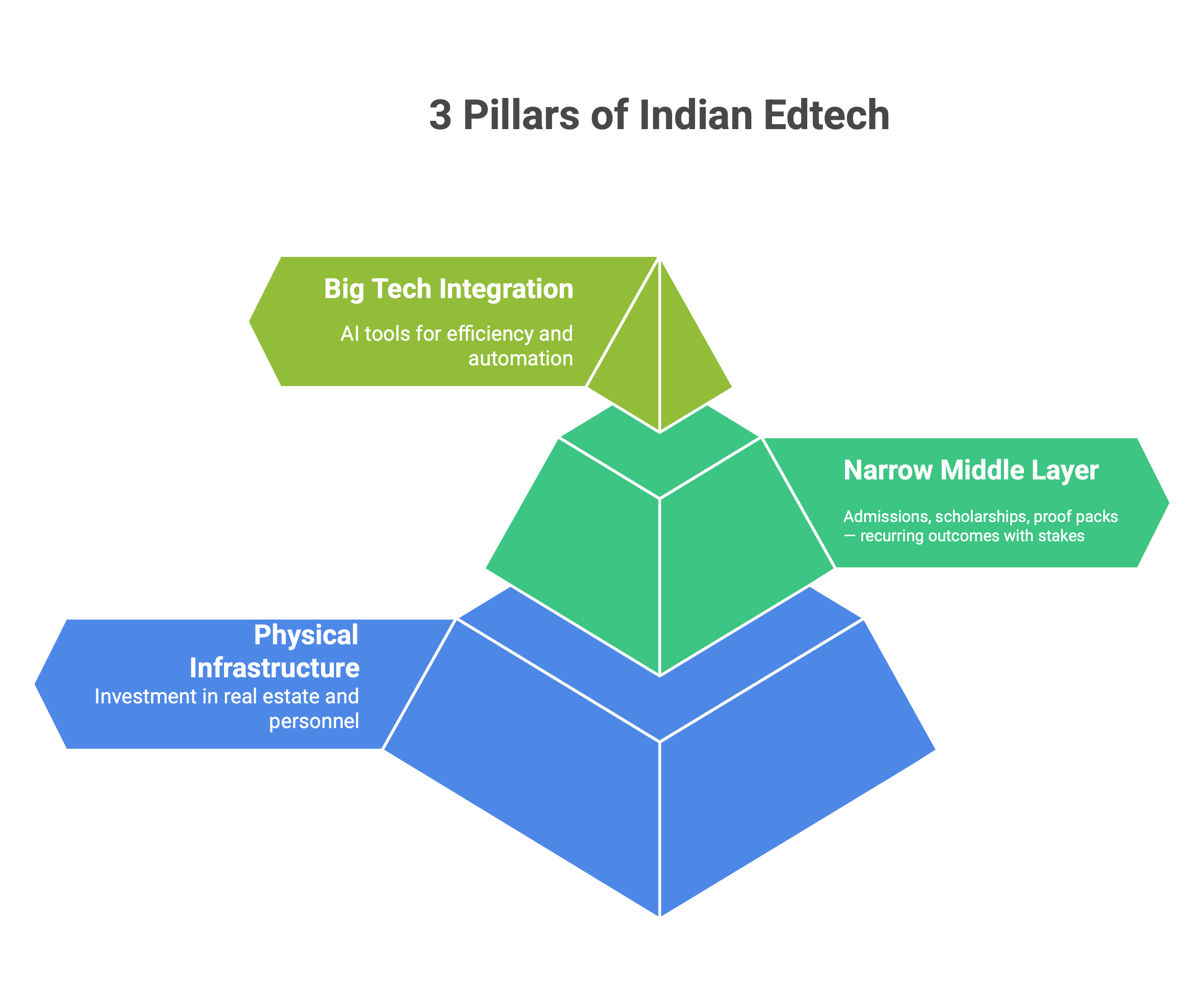

For a few years, Indian edtech was defined by surging online brands and billion-dollar bets. That phase has cooled. Capital has rotated into offline centres, where scale means more buildings and teachers. At the same time, Big Tech is flooding campuses with low-cost licences for AI assistants. Between these two edges, it is fair to ask: is there still room for startups?

Our answer is cautious. The offline play is crowded and cash-hungry. The tool layer is cheap, bundled, and dominated by global vendors. Yet a narrow middle remains — places where institutions must publish results, where errors have visible costs, and where digital workflows already repeat each year. This is why we reopened our work on Indian edtech now.

What changed at both edges of the market

Two movements reshaped Indian edtech in the past two years. On one side, the large consumer brands that built their reputation online are now expanding aggressively into offline centres. Unacademy continues to add locations, PhysicsWallah has crossed 150 centres across many states, and Allen remains the national test-prep benchmark. This is a scale game tied to buildings, teachers, and city-by-city execution. It absorbs capital, but growth remains linear and cash-intensive.

On the other side, AI tools have arrived cheaply and at scale. OpenAI has announced nearly 500,000 ChatGPT licences in India for 2025. Microsoft’s Copilot for Education and Google’s Gemini-powered Workspace features are now bundled directly into campus workflows. These assistants land easily, spread quickly, and cost little — but they are controlled by Big Tech, not by startups.

Between these two edges sits a narrow middle that looks less crowded. This is where institutions already perform recurring digital work — admissions lists, scholarship disbursement logs, accreditation filings — and where errors carry visible downside. The pattern resembles what we observed in enterprise data infrastructure after Salesforce’s $8B Informatica deal: once the pipes are taken by giants, value shifts to the system that turns messy inputs into accepted outcomes (Accrezeo, 2025). Edtech may now follow a similar path, with room for startups in this middle layer.

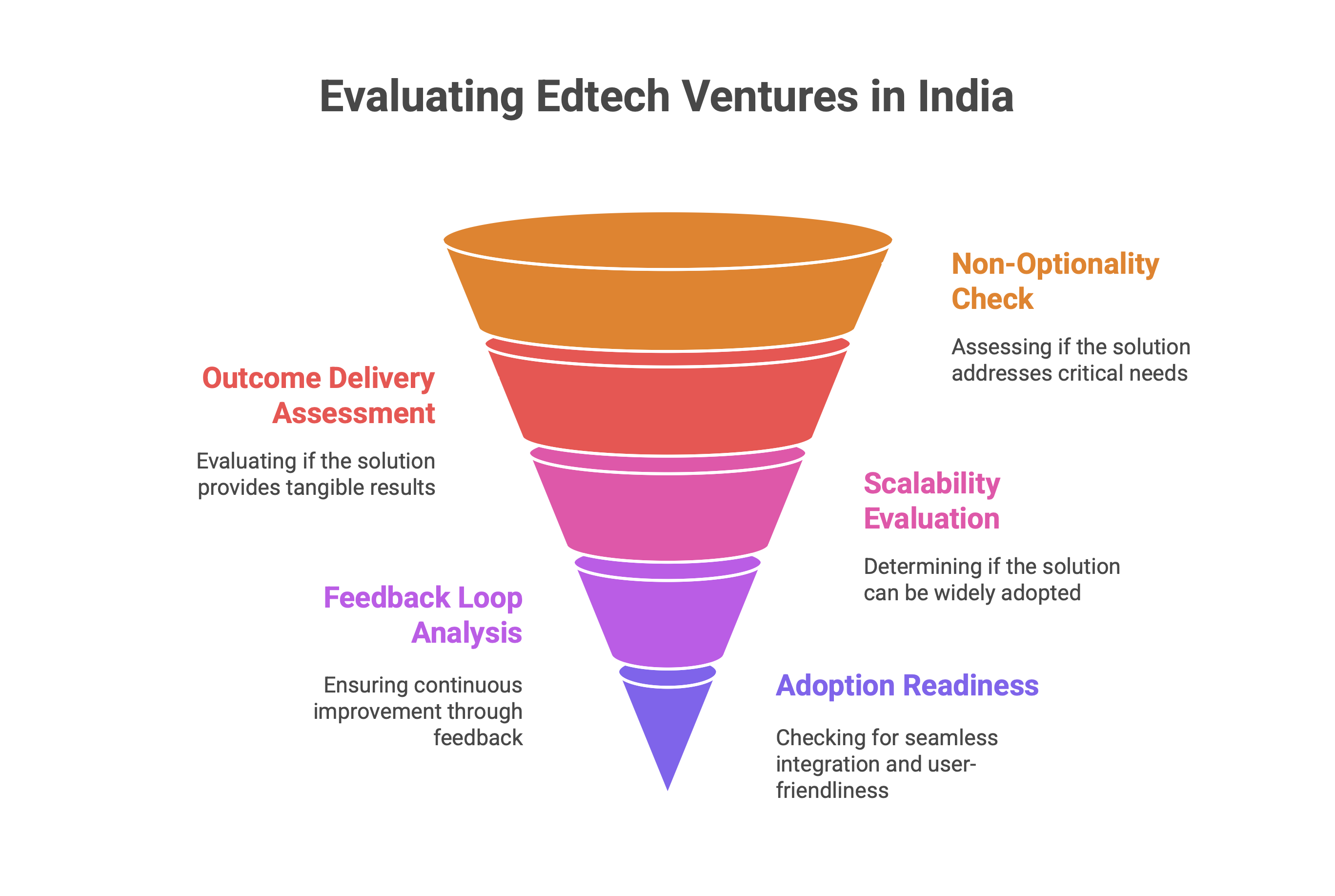

The middle layer that still looks open

If the edges are spoken for, what remains is the narrow middle where institutions must produce results that others accept. Unlike offline centres, this work is not about buildings or teachers. Unlike Big Tech tools, it is not about generic assistance. The middle is about outcomes: an admissions list that can be posted without back-tracking, a scholarship disbursement that passes audit, or an accreditation pack that survives review. These are outputs that matter because failure is visible — intakes pause, fee revenue is at risk, or credibility suffers. We have seen similar dynamics in LegalTech, where the value lies not in drafting help but in filings and proof packs that courts and regulators actually accept (Accrezeo, 2025).

This layer is not speculative. National portals already handle tens of thousands of filings each year, with many kept live for three years (NIRF 2024). Institutions file annual quality reports, and larger dossiers come up on multi-year cycles. While coverage is below half of all universities and colleges today (NAAC 2024), the rhythm is established. The workflow repeats, the downside of mistakes is clear, and the formats are public. That combination gives the middle its potential.

For startups, the opportunity is to package this dull but critical work into software that lands light — files in, checklists and timestamps out — and earns trust by handling vernacular documents and keeping published links live. It is not as large or visible as consumer edtech once was, but it sits where willingness to pay is real.

Admissions and scholarships show the strongest fit

Among the recurring digital workflows in Indian higher education, admissions and scholarships stand out as the most credible lanes for software. These are processes that repeat every year, follow written rules on reservations and tie-breaks, and face objections the moment lists are posted. When they slip, the downside is immediate: intakes pause, a full cohort’s fee revenue is lost, and institutions risk credibility. That visible cost creates a willingness to pay that lighter, optional workflows rarely trigger.

Scholarships follow the same rhythm. They run on documented rules, generate public objections if results are inaccurate, and often involve proofs in local languages. On their own, scholarships may look like another one-office tool. Paired with admissions, however, they reuse the same steps and accepted formats. That reuse raises the ceiling, turning what looks like two mid-sized categories into one stronger lane.

By contrast, accreditation filings, while real, tend to cap out when sold to one office at a time. They can support a business but likely sit below a classic venture bar. Exam-day incident reporting is even harder to scale — it comes in short bursts, varies widely by centre, and pulls vendors into custom projects.

Size estimates help set perspective. On simplified assumptions, admissions and scholarships together could support ₹100–₹250 crore a year at national scope, while accreditation as a stand-alone lane sits closer to ₹150–₹300 crore a year(AISHE 2024; NIRF 2024). These ranges suggest real headroom, but also show why scale depends on reuse across offices or state-level buyers rather than one-by-one sales.

What this means now

The last cycle of Indian edtech suggests a reset. Consumer-facing apps raised billions and, in most cases, under-delivered. At the other edge, AI assistants are arriving cheaply at scale, with Big Tech distributing licences in the hundreds of thousands. Those lanes are crowded and unlikely to be won by startups.

The middle is different. Here, the work that matters is not optional or experimental — it is outcome-level. Admissions lists, scholarship rolls, and accreditation packs are published on fixed calendars, carry reputational cost if they slip, and already repeat each year. That combination makes them credible software lanes.

The challenge is scale. Sold to one office at a time, even strong workflows like accreditation may cap out. The venture case emerges only when the same accepted outcome is reused across multiple teams inside an institution, or when a larger buyer — a state counselling portal or a university group — can purchase once for many. Without that scope, the lane remains valuable but mid-sized.

For founders and investors, the implication is clear: treat the edges as spoken for, and look instead at teams that can already point to an accepted, published result and show early reuse across offices. Anything else may still be a respectable business, but it will struggle to clear the bar for venture capital.

How investors and founders can judge what’s worth backing

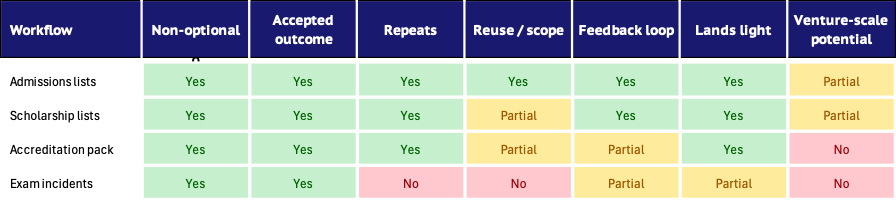

The hard part in Indian edtech is not spotting activity but deciding what can compound. For that, a simple screen helps.

The first test is whether the work is non-optional. Admissions lists and scholarship rolls must be published on time; if they slip, seats go empty and revenue is lost. That visible downside drives willingness to pay.

The second is whether the tool delivers an accepted outcome, not just assistance. Officials budget for the version they can post or file — the admissions list with tie-break notes, the scholarship roll with checks complete, the proof pack that passes review. Drafts and helpers are easier to swap out.

The third is scope. Wins that stay inside one office tend to cap quickly. Venture scale usually needs reuse across multiple teams, or purchase by a wider buyer such as a university group or a state counselling portal.

The fourth is the presence of a feedback loop. Products get stickier when objections fall cycle after cycle, when time from draft to publish shrinks, or when logs reduce rework. If every year starts from scratch, pricing pressure follows.

Finally, adoption depends on the landing. Tools that ride existing logins, shared drives, and spreadsheets face less resistance than heavy installs. In India, getting vernacular documents right and keeping links live for months are also part of building trust.

Where we stand on Indian edtech today

Indian edtech no longer looks like the wide-open consumer play it was during the funding boom. The offline edge is now tied up by large brands with heavy capital and linear growth. The tools edge is being absorbed by Big Tech, distributing licences at a scale no startup can match.

That leaves the middle — narrow but real. Admissions and scholarships, in particular, fit the shape of repeatable, outcome-level workflows. They show willingness to pay, generate visible downside when they fail, and could support ₹100–₹250 crore in national revenue if reuse or state-level buyers emerge. Accreditation is meaningful but smaller, and exam incidents remain too spiky to standardise.

So where do we stand? The whitespace is real, but venture potential depends on whether startups can push beyond single-office sales. Without that scope, the middle layer stays valuable but mid-sized. With it, Indian edtech may still yield investable companies — not by competing with offline infra or Big Tech tools, but by owning the dull, recurring outcomes others rely on.