Why do investors keep funding fragile business models in India?

Over the past year, several well-known funds have backed startups that most people would call fragile—businesses with thin margins, long payback cycles, or high return rates that still manage to raise large rounds and expand quickly. Two examples stood out early. In Fast Fashion Q-Commerce: What Founders Are Testing and Investors Are Missing, we saw how speed was being used as proof of demand even when the numbers stayed weak. In House Help Digitisation: If Citywide Scale Is Hard, Where Does the Platform Compound?, we found the same behaviour in a very different market—high-frequency, low-margin human services that still drew patient capital.

These examples made us pause. It seemed unlikely that experienced investors were ignoring basic economics. Something else was guiding these choices—perhaps a belief that certain weak points would repair themselves over time, or that behaviour and timing were shifting faster than the numbers could capture.

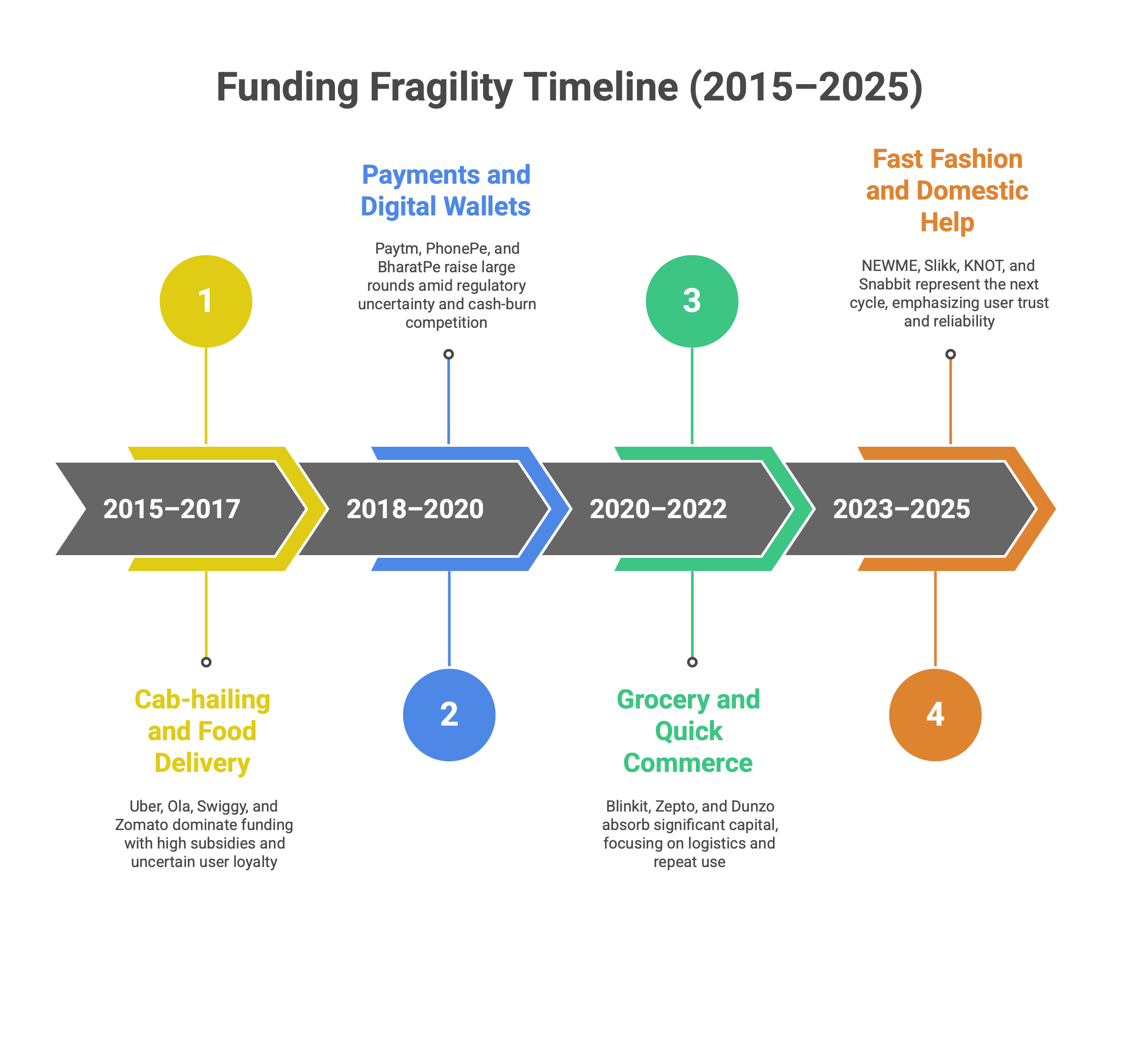

This question is not new. Each funding wave in India—cabs, food delivery, payments, grocery, and now fast fashion—has followed the same arc: fragile economics at the start, strong funding in the middle, and gradual testing of whether the system can stabilise. The pattern keeps returning, only in new verticals.

That repetition is what caught our attention. If capital continues to flow into businesses that start weak but show fast learning, then fragility may not be an exception—it may be part of how markets in India mature. Understanding why that happens again is what led us to look closer at how venture money is moving today, and what it reveals about investor logic beneath the surface.

That repetition is what caught our attention. If capital continues to flow into businesses that start weak but show fast learning, then fragility may not be an exception—it may be part of how markets in India mature. Understanding why that happens again is what led us to look closer at how venture money is moving today, and what it reveals about investor logic beneath the surface.

How the pattern showed up again across sectors

When we studied the current wave of funding alongside earlier ones, the behaviour of capital started to look familiar. Across very different categories—fast fashion, domestic help, and even some AI-driven tools—the same pattern kept appearing. Companies with fragile economics were still able to raise meaningful rounds, and the language used to explain those rounds sounded almost identical. Founders spoke about building habits, earning trust, and reaching density before chasing efficiency. Investors described their cheques as buying proof or training the market.

This repetition suggested that these were not isolated bets but part of a larger investment rhythm that India has seen before. The sectors and products have changed, but the funding logic hasn’t. The same kind of capital continues to flow into models that look weak in the short term, driven by the belief that certain weak points—cost, trust, or timing—can fix themselves as the system matures.

What stood out was not new behaviour, but how clearly the pattern reappeared. Fragility, once treated as a warning sign, now seems to have a recognised place in the investment process. Each cycle of funding is used to see whether a system can improve its own signals fast enough to justify more capital.

To understand how investors decide which fragile models are worth backing, we then looked at the kinds of weakness they seem most willing to underwrite.

What kinds of fragility do VCs knowingly underwrite?

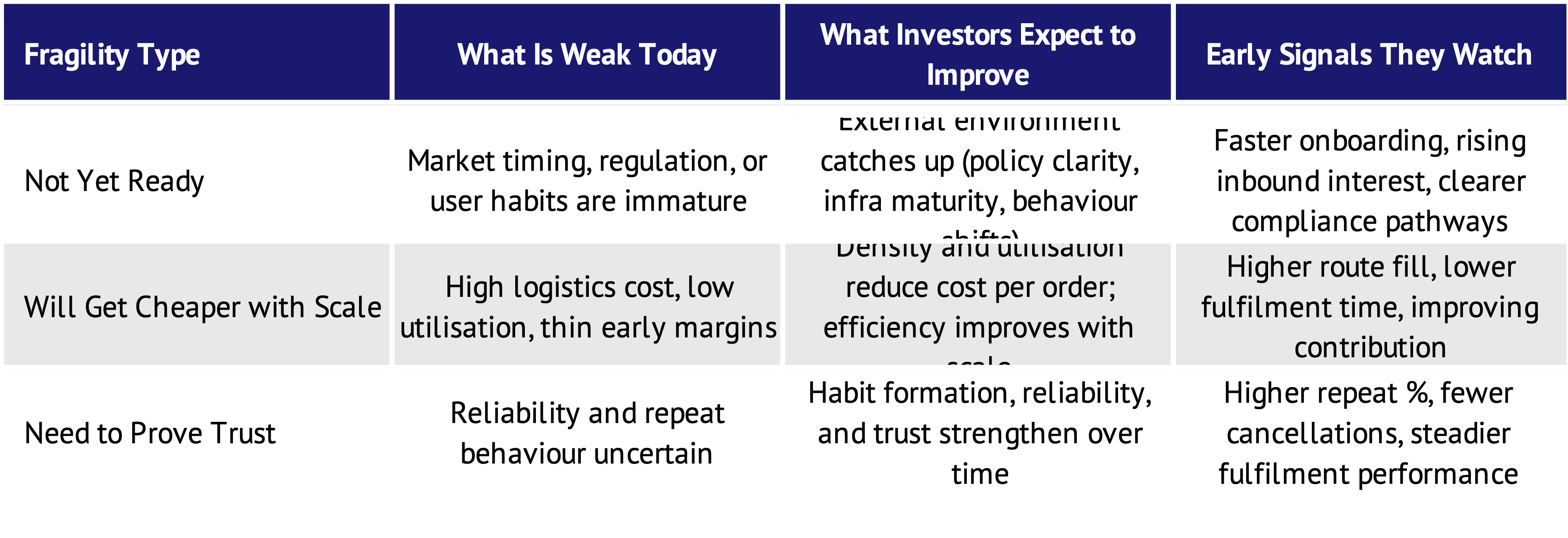

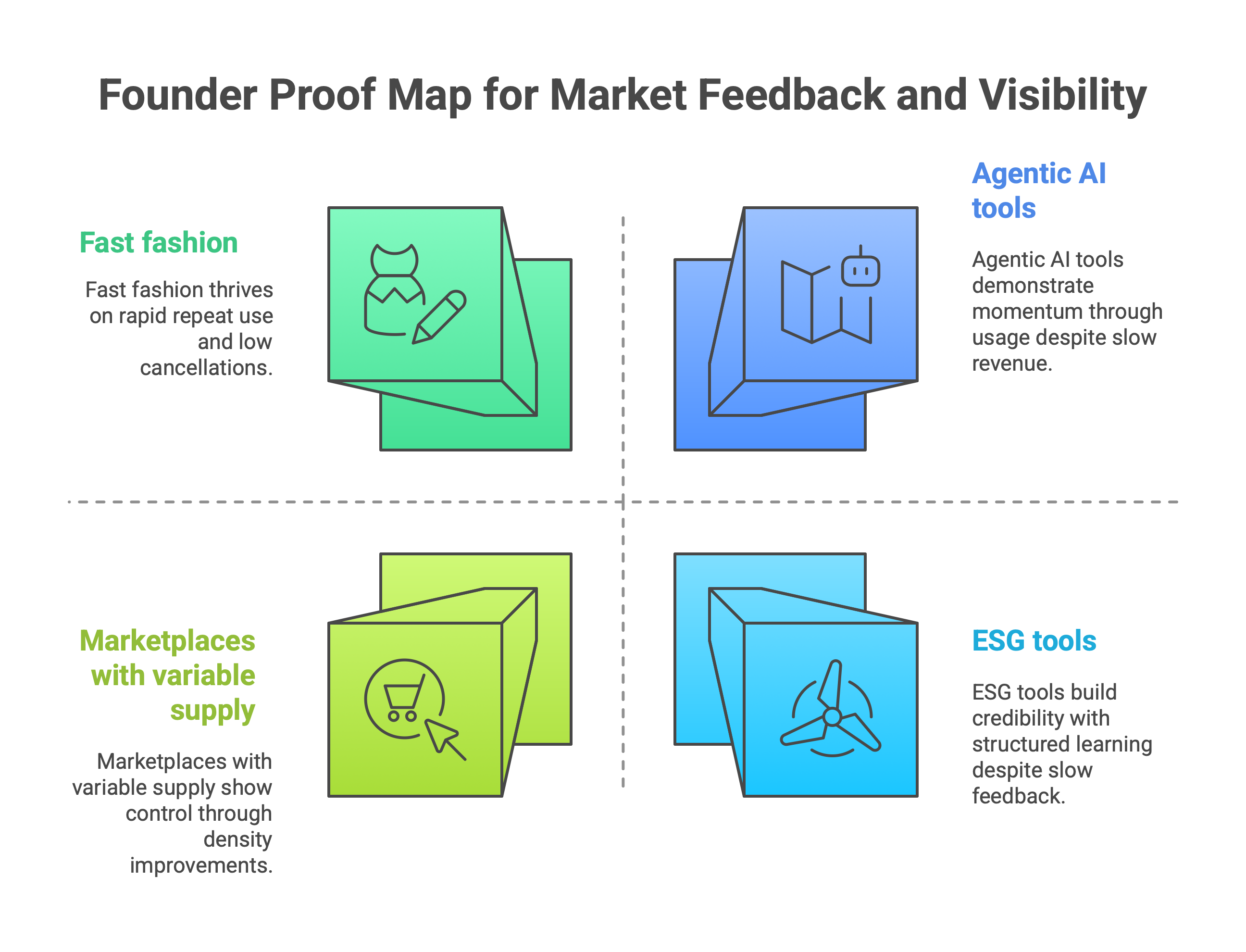

When we compared different sectors, it became clear that investors don’t treat all fragile models the same way. The weakness they are willing to fund falls into a few broad types, depending on what they believe will improve with time.

The first is “not yet ready” fragility. These are startups that rely on outside factors maturing—like regulation, infrastructure, or user habits. ESG or carbon-reporting tools often fall in this group. They look small or slow today, but investors expect the environment around them to catch up and make their product essential. The weakness here is timing, not structure.

The second is “will get cheaper with scale” fragility. These are models that burn money early because efficiency depends on size. Logistics and fleet networks—like the early phases of Delhivery or Rivigo—fit this pattern. As routes fill and utilisation rises, each transaction costs less. The weakness is temporary because scale can fix it.

The third is “need to prove trust” fragility. These are startups where the product works but users or partners don’t yet believe it will stay reliable. Fast-fashion delivery and domestic-help platforms fall into this category. They spend early money on building trust and repeat behaviour rather than profit. The weakness is belief, not demand.

Seeing fragility through these lenses helps explain why certain businesses keep getting funded despite weak numbers. Investors aren’t ignoring the risk—they’re making a judgment about which kind of weakness can heal itself over time. That framework shaped how we read the next set of examples, starting with fast fashi

How are investors using speed as proof in India’s fast-fashion market?

Funding for Indian fashion startups has fallen sharply—from about $611 million in 2023 to roughly $56 million in 2025. Most investors have turned cautious, yet a few companies that blend fast fashion with quick delivery continue to raise meaningful rounds. The most visible among them are NEWME, Slikk, and KNOT—each testing whether faster delivery can serve as early proof of control and trust.

NEWME has raised about $24 million and now runs roughly 14 stores that also serve as fulfilment hubs. About 90 percent of its sales come from its top 10 percent of SKUs, and it reports an ARR close to $6 million. The idea is that owning stores and private-label stock will improve margins and lower returns over time. For now, costs stay tight: frequent inventory refresh and city-wide fulfilment add expense, so repeat purchases and faster turns are critical to maintaining contribution.

Slikk has raised around $13.5 million from Lightspeed and Nexus. It offers 60-minute delivery and a “Try Before Buy” feature. KNOT, a newer entrant backed by Kae Capital, is testing the same promise through AI try-ons and doorstep trials in Mumbai. Though their models differ, all three are essentially testing the same hypothesis—whether small, linked gains in delivery cost, return rate, and repeat behaviour can turn fragile economics into a stable loop.

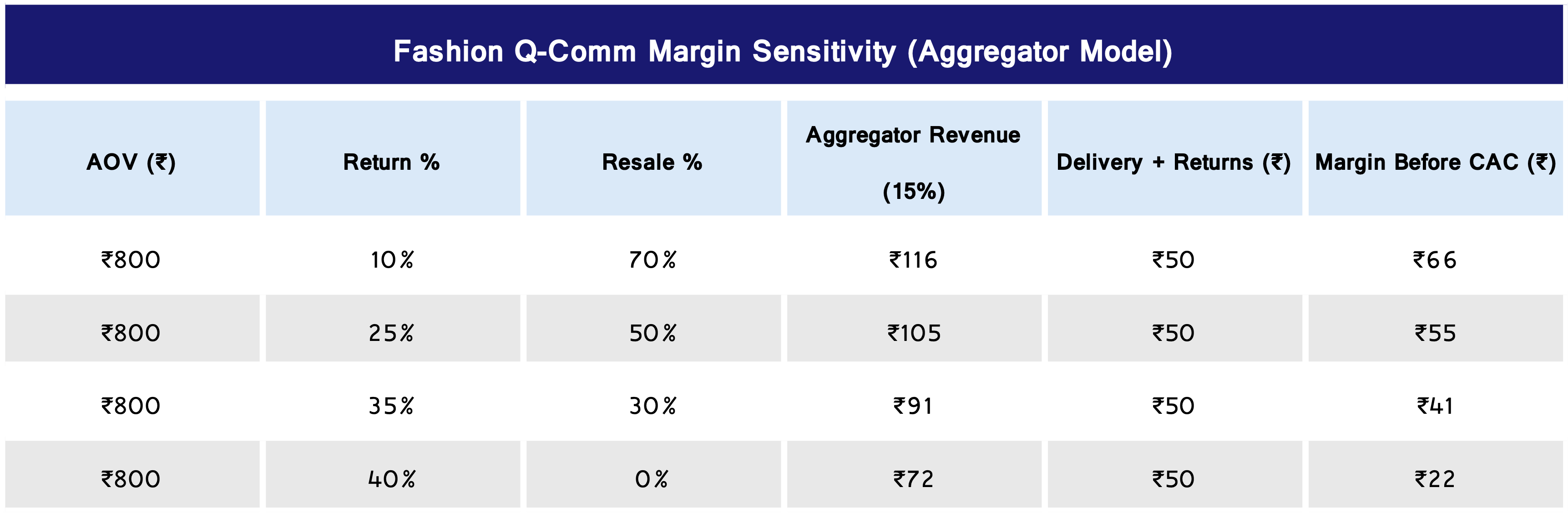

The unit economics sensitivity table in this blog illustrates that even under conservative assumptions, contribution margins remain slightly positive—ranging from ₹22 to ₹66 per order before marketing costs. The fragility lies not in being unprofitable but in being too thin. Once customer acquisition and discounting are factored in, that buffer can disappear unless multiple levers move together. Returns must fall, resale or repeat use must rise, and AOV must hold steady. Investors seem to be betting that these levers will align fast enough for the model to stay above water.

Across players, the details vary, but the direction is consistent. This isn’t a search for profit yet; it’s a search for stability. Capital is being used to test whether speed and habit can build the kind of trust that keeps contribution margins positive over time.

How are investors using structure as proof in India’s domestic-help market?

The domestic-help sector shows a different kind of fragility. Demand exists across cities, but reliability and continuity remain uncertain because most of the work still happens informally. New platforms are trying to formalise this by adding structure—training, matching, and payout systems that make the service predictable for both workers and households.

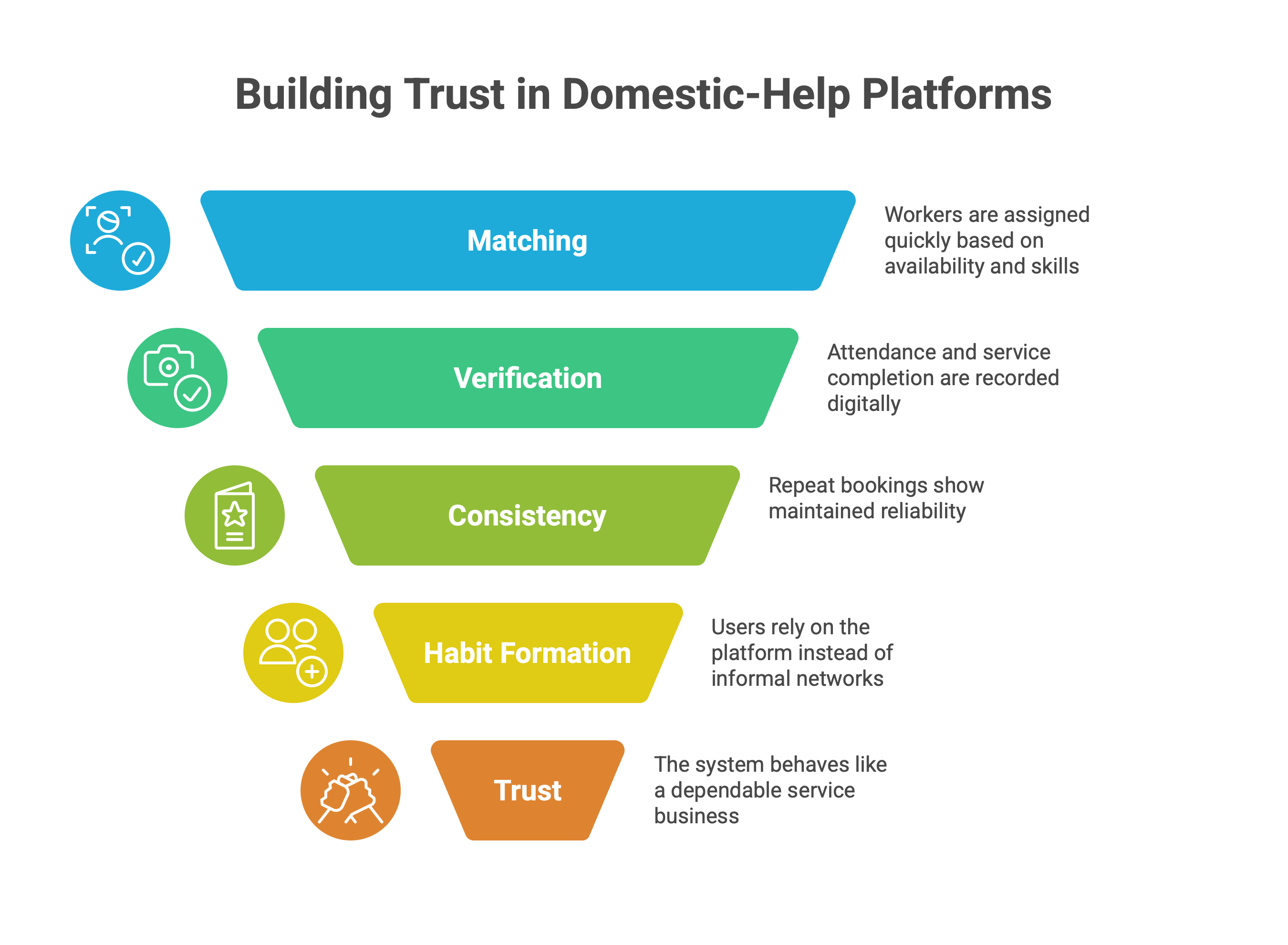

Urban Company’s Insta Help and Snabbit are testing this idea through slightly different lenses. Insta Help promises help within about fifteen minutes and already handles hundreds of thousands of monthly orders. It uses instant supply to show that the market can run on verified, traceable service rather than informal networks. Snabbit, a newer entrant, is testing whether that same logic can hold at smaller scale. It promises help within thirty minutes, positions itself as a faster alternative to agency-based matching, and relies on verified attendance, payout traceability, and replacement guarantees to build trust.

Early data shows that user churn after the first month remains high, but repeat among retained users is strong. The uncertainty is not about demand—it’s about whether reliability can scale without heavy on-ground costs. If retention improves, utilisation and worker earnings could rise meaningfully; if not, retraining and replacement costs will keep eroding contribution.

Investors appear to be backing these platforms on the belief that a certain kind of structure—clear payouts, verified attendance, and transparent replacement—can make informal labour behave more like a service business. Whether that confidence holds is still open, but the funding logic looks familiar: patient money underwriting early fragility in the hope that proof will appear as systems mature.

What does this tell us about how capital behaves?

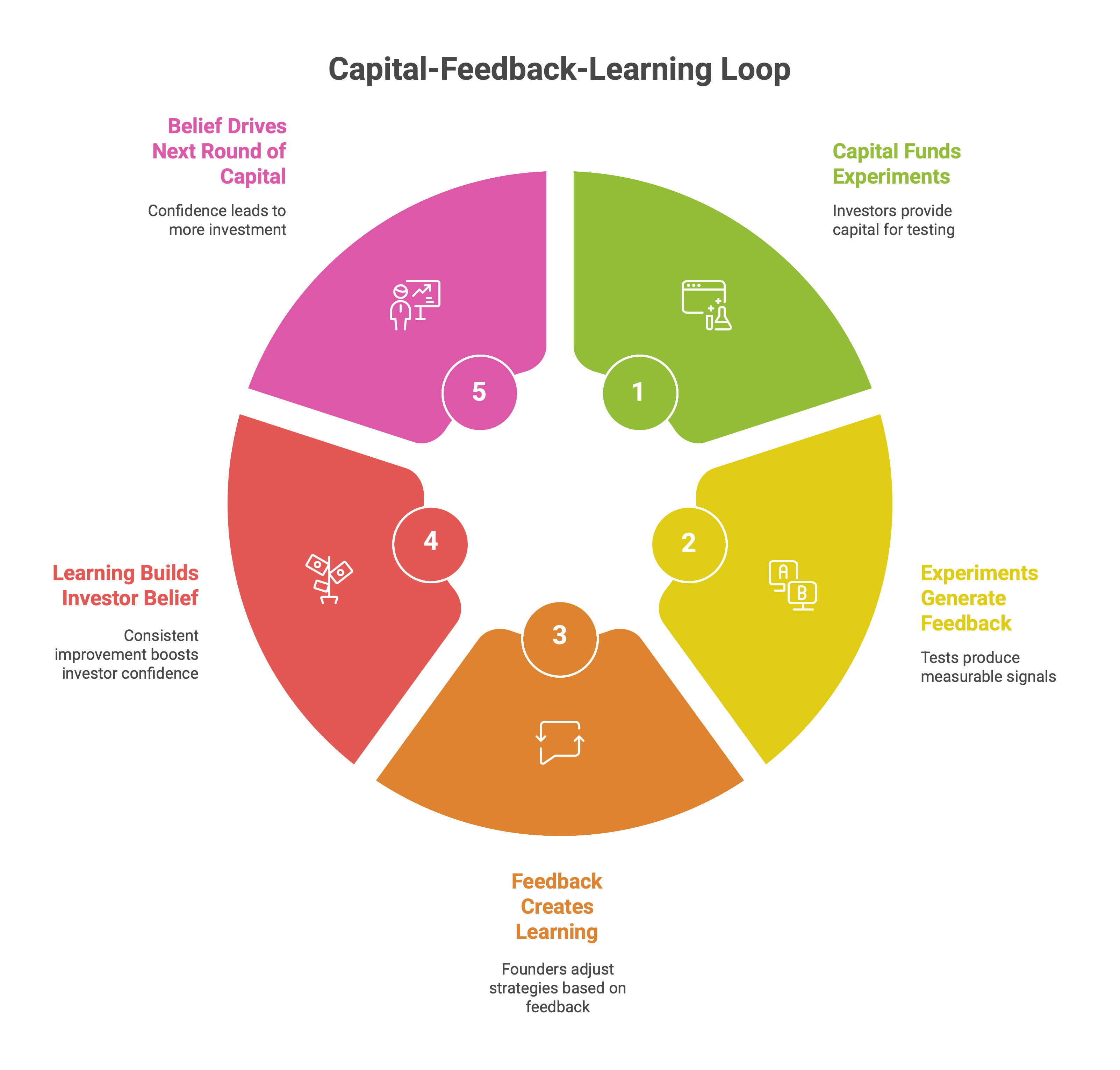

Across cycles, the same pattern keeps returning. Whether in fast fashion, domestic help, or earlier categories like food delivery and cabs, investors have continued to fund models that begin weak but seem capable of improving fast. Only a few of those markets eventually become sustainable, yet the logic behind early funding stays consistent: capital is used less to buy profit and more to buy learning.

In these fragile systems, every round becomes a way to test whether repetition can turn weakness into stability. When investors see data improving—faster delivery, steadier retention, fewer cancellations—they update their belief and stay patient. This is not certainty; it is learning in motion. The assumption is that if feedback comes quickly enough, the system will eventually repair itself.

We saw this most clearly in markets where signals appear in real time. Consumer categories such as fashion or services generate data daily, allowing investors to track progress within a single fund cycle. B2B or enterprise software, by contrast, often shows results more slowly. These businesses may be stronger in fundamentals but offer fewer interim signals, which makes conviction harder.

Agentic-AI and LLM-based products sit somewhere in between. Though they sell to businesses, adoption often begins bottom-up, through small teams or self-serve use. That pattern produces feedback more like a consumer product, which helps investors apply the same short learning cycles they use elsewhere.

In fast-feedback markets, large reserves of capital can also create short-term advantage. Well-funded companies can run more experiments, reach density faster, and buy time for their learning loops to strengthen. But the same logic has limits. When capital is abundant, it can mask weakness; when it tightens, only the models with genuine self-correction survive.

Taken together, these signals suggest that investors appear most comfortable in markets where fragility produces fast feedback. It’s not about optimism—it’s about probability. Venture capital in India seems to prefer places where it can watch systems learn quickly, adjust exposure, and let time decide which ones endure.

What should founders take away from this?

For founders, the main lesson is that early fragility doesn’t automatically close the door to funding. What matters more is whether that fragility can be measured and whether the key signals are improving over time. Investors seem to stay patient with companies that can show steady movement on a few core variables—repeat use, retention, fulfilment time, or cost per order—even if the overall numbers still look weak.

In fast-feedback sectors like fashion or home services, that learning shows up quickly. Each cycle—an order, a delivery, a repeat visit—offers data that helps prove the system is improving. A startup that can show higher repeat rates or lower cancellations month by month builds credibility, even if it’s not yet profitable. The evidence investors look for is consistency of progress, not perfection.

In slower or more complex models such as enterprise SaaS or ESG tools, the signals take longer. Here, the challenge is to make learning visible before big revenue arrives. Showing faster onboarding, shorter sales cycles, or higher pilot conversion can demonstrate that the system is still learning, even when absolute numbers move slowly.

Capital depth also changes how this plays out. A well-funded company can run several experiments at once, compressing time to proof. Smaller teams often have to do it in sequence—prove one lever, document the result, and use that learning in the next raise. Investors reward that clarity. They respond better to founders who can show how each cycle of work reduces uncertainty than to those promising scale without evidence.

It also helps to remember that investors themselves work within constraints—fund timelines, bandwidth, and portfolio balance all shape their choices. A “no” or a delay often reflects structure, not disbelief. The practical takeaway is simple: make progress visible, link every experiment to a clear learning, and show that fragility is a system still teaching itself how to work.

Where can this logic break down?

The idea that capital can underwrite fragility works only as long as the system keeps learning. Once the signals slow or stop improving, patience fades quickly. In categories like fast fashion or domestic help, that risk is built into the structure. When order density or utilisation plateaus, small gains no longer change the math, and what once looked like controlled burn starts to resemble a permanent loss.

Another risk is mistaking visibility for strength. Fast feedback can create false confidence—metrics may rise sharply in early months but flatten once the easy segments are served. Many sectors once backed on quick proof—grocery delivery, hyperlocal logistics, gig platforms—have shown this pattern. The surface data looked strong, but learning slowed before the economics caught up.

A third weak point is overestimating behaviour change. Speed and convenience can create short bursts of demand, but sustaining them needs reliability and trust. If those deeper layers don’t form, repeat use collapses. Models built on high fixed costs or subsidies feel this collapse suddenly and find it hard to recover.

The investor system itself also has limits. Fund horizons are short, and capital rotation is constant. Even startups showing progress can struggle if markets tighten or priorities shift. Belief alone doesn’t guarantee follow-on money.

This logic—that fragile systems can teach themselves to work—only holds if proof compounds faster than burn. When feedback loops weaken or learning becomes too costly to sustain, the same factors that once justified optimism can turn into reasons to exit.

Where does that leave us now?

When we first asked why investors keep funding fragile models, the question seemed to be about optimism. It turned out to be more about process. Venture capital, at its core, funds systems that can learn faster than they fail. Speed, density, or structure are only the tools used to test that ability.

Across sectors—from fast fashion to domestic help—the common thread is not confidence in outcomes but belief in repetition. Investors appear to be testing whether weak economics can strengthen through constant learning, and whether human or operational friction can eventually be standardised.

For founders and funds alike, the lesson is that fragility is not the opposite of strength; it is often the stage before clarity. What separates the two is how clearly a system can show that it is improving. The cycle continues until that improvement stops—or until the proof becomes strong enough to stand on its own.

(Visual Placeholder: Napkin summary graphic—timeline showing how fragility → learning → proof → clarity across sectors.)

At Accrezeo, we work closely with early-stage founders and investors who are building in markets that don’t look easy yet—but have the right signals of learning. If this line of thinking resonates with you, or you’re testing a similar thesis, we’d be glad to exchange notes.