Hose Help Digitization : Why This Vertical, Now”.

Houae help in India is one of the country’s largest and most routine household spends. A back-of-the-envelope view places the annual wage pool around $30–40B. The size alone makes it a category that investors and founders cannot ignore.

Unlike many sectors where digital adoption is still about creating new habits, here the habit already exists. Millions of households rely on daily help, and the service repeats by default. The question is not whether people will use it again tomorrow — they almost certainly will. The question is whether that steady demand can translate into a business that compounds on software.

The timing looks more favourable than it did a decade ago. Payouts are simpler with UPI, Aadhaar eKYC makes verification easier, and basic insurance or credit products are within reach. Housing societies in many cities now use digital gate logs, which at least creates a base for record-keeping. Newer companies are trying on-demand models with trained, verified workers. Older agency and subscription formats still operate in parallel. Together, these signals suggest the space is being tested again under different conditions.

This is the backdrop. The next step is to look closely at what is happening on the ground — and whether week-to-week coordination is staying on software long enough to matter.

What’s Happening on the Ground in HouaeHelp

The day-one problem — finding a worker — looks solvable. Where things start to stretch is after the first match. Households and workers need to agree on time windows, manage absence or replacement, and keep payments predictable. Discovery alone does not solve these routines; coordination does.

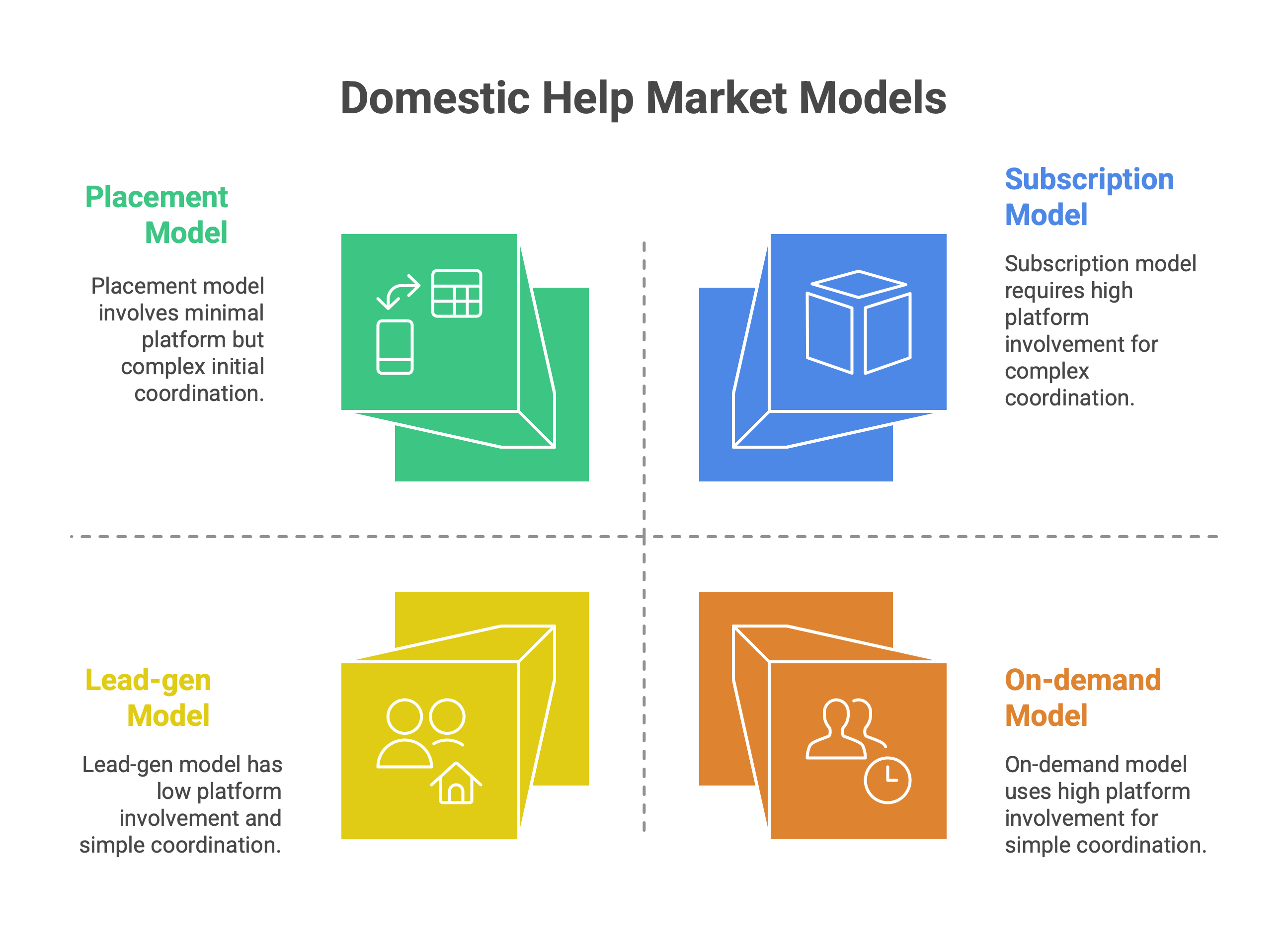

What we see in India today is not one single market shape, but a few different ones. Agency or placement models help families hire and then mostly step back. Subscription or retainer models hold a fixed slot, while wages are paid directly. On-demand services sell time by the hour for ad-hoc chores. Lead-gen platforms act more like classifieds, charging a one-time or success fee. These shapes often coexist in the same city — sometimes even in the same building.

Across these formats, frictions show up again and again. Most households want help in the morning or early evening, which compresses demand into tight windows. Visit lengths vary — some homes need just a quick clean-up, others need multi-hour blocks — which makes scheduling difficult. Even simple proof of attendance is not uniform: different societies ask for different formats at the gate, creating extra local work.

Technology helps, but unevenly. UPI and instant payouts lower cash friction. Aadhaar makes background checks easier. Gate apps record entries in many societies, though formats differ from one to the next. Digital records of who came and when may help keep coordination on-platform, but take-up is still patchy.

This mix points to a practical test: can enough of the weekly routine — scheduling, proof, and payouts — actually stay on software? If it does, compounding may be possible. If it does not, discovery may remain the thin surface layer.

Competitive Landscape in Domestic Help Digitisation

A handful of companies are testing different shapes of the market, each with its own bet on how coordination and cash flow should work.

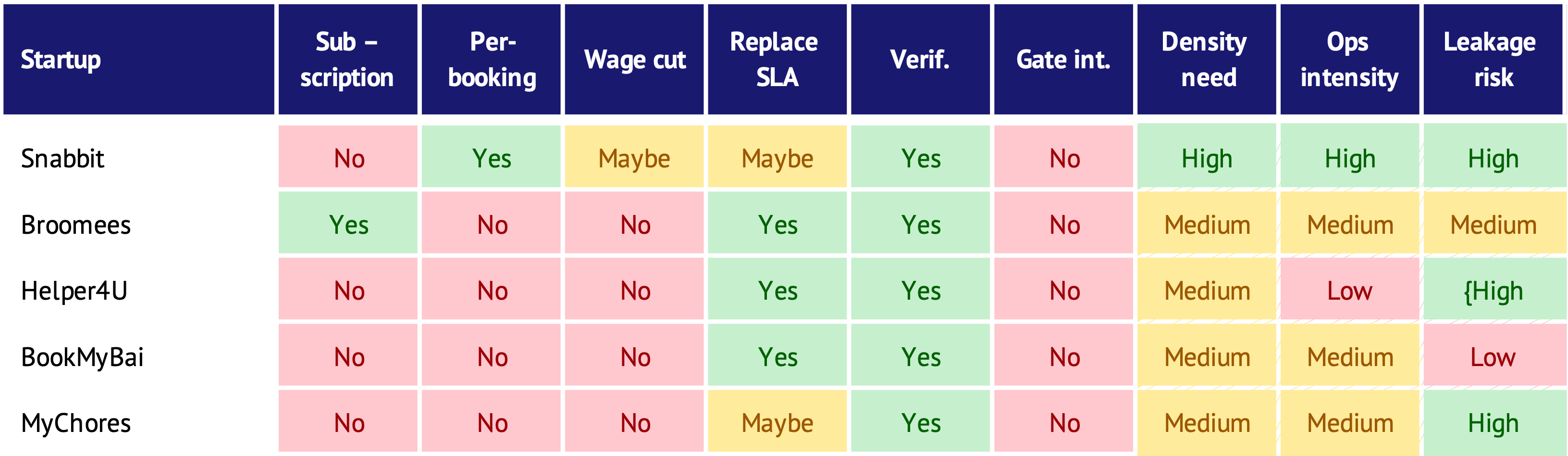

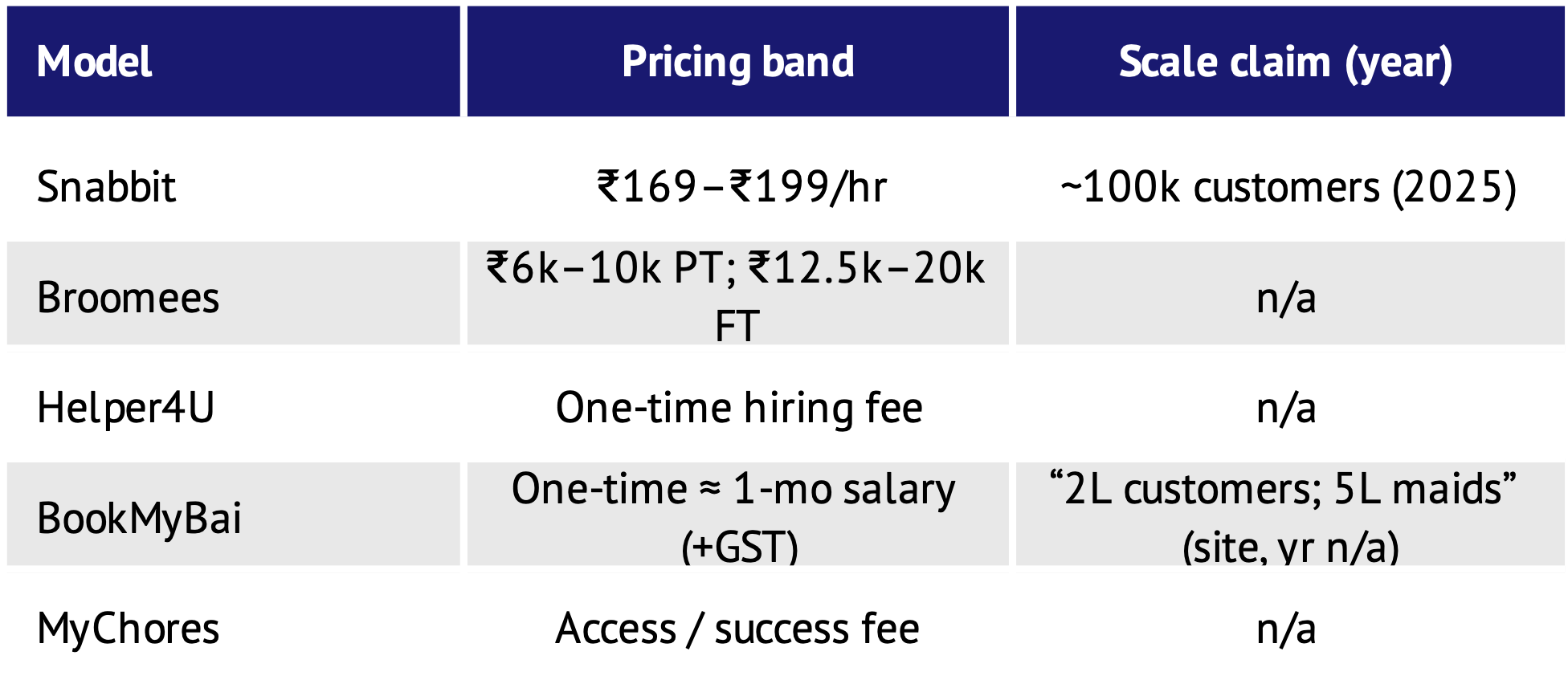

Snabbit runs a per-booking model with hour-based pricing, typically around ₹169–₹199 per hour. Company mentions suggest about 100,000 customers and 2,500 workers across Mumbai, Bengaluru, Gurugram, and Thane. Retention was reported in the mid-30s, though definitions were unclear. This looks more like a “maid-on-leave” or episodic service than a daily replacement.

Broomees offers a subscription path, with households paying workers directly and the platform charging for verification and replacements. Pricing bands sit near ₹6,000–₹10,000 per month for part-time and ₹12,500–₹20,000 per month for full-time across Delhi-NCR, Bengaluru, and Pune. The pitch is predictability: the value depends on schedule adherence and replacement speed.

Helper4U acts as a lead-generation platform. Families pay a one-time fee near the point of hire, with a six-month replacement and simple refund option. Breadth of searchable profiles is the main draw, but most week-to-week coordination happens off-app. Public scale numbers were not reliable.

BookMyBai follows a placement model. It charges an upfront fee of roughly one month’s salary plus GST, with a multi-month replacement window. The site claims about 200,000 customers and 500,000 maids across cities. Revenue comes at placement, so the model relies more on screened supply and steady new demand than on ongoing engagement.

MyChores screens and shortlists profiles for families across cities, operating more like a matcher than an on-demand service. Commercially it looks closer to an access or success-fee model. Public data on active cities or volumes was not clear.

Adjacents also matter. Housejoy shows that one-off home services like cleaning or repairs can be booked online, but daily domestic help behaves differently. Gate apps such as MyGate or NoBrokerHood manage entry logs and documents in many societies, though formats differ and proof does not travel uniformly.

Business-Model Scalability Snapshot

The key question for domestic help platforms is not whether households need the service — that part is obvious. The question is which business shapes can compound, and what has to line up for that to happen.

Placement or agency models scale when there is a steady inflow of screened workers and time-to-fill stays predictable. Because fees land upfront, leakage after hire matters less, but long replacement times or weak supply pools can slow growth.

Subscription or retainer paths depend on routines holding. Platforms need schedule adherence above 80–90% and replacements that arrive quickly when a slot breaks. Reliability week to week is the product; operations must stay light enough that margins do not erode.

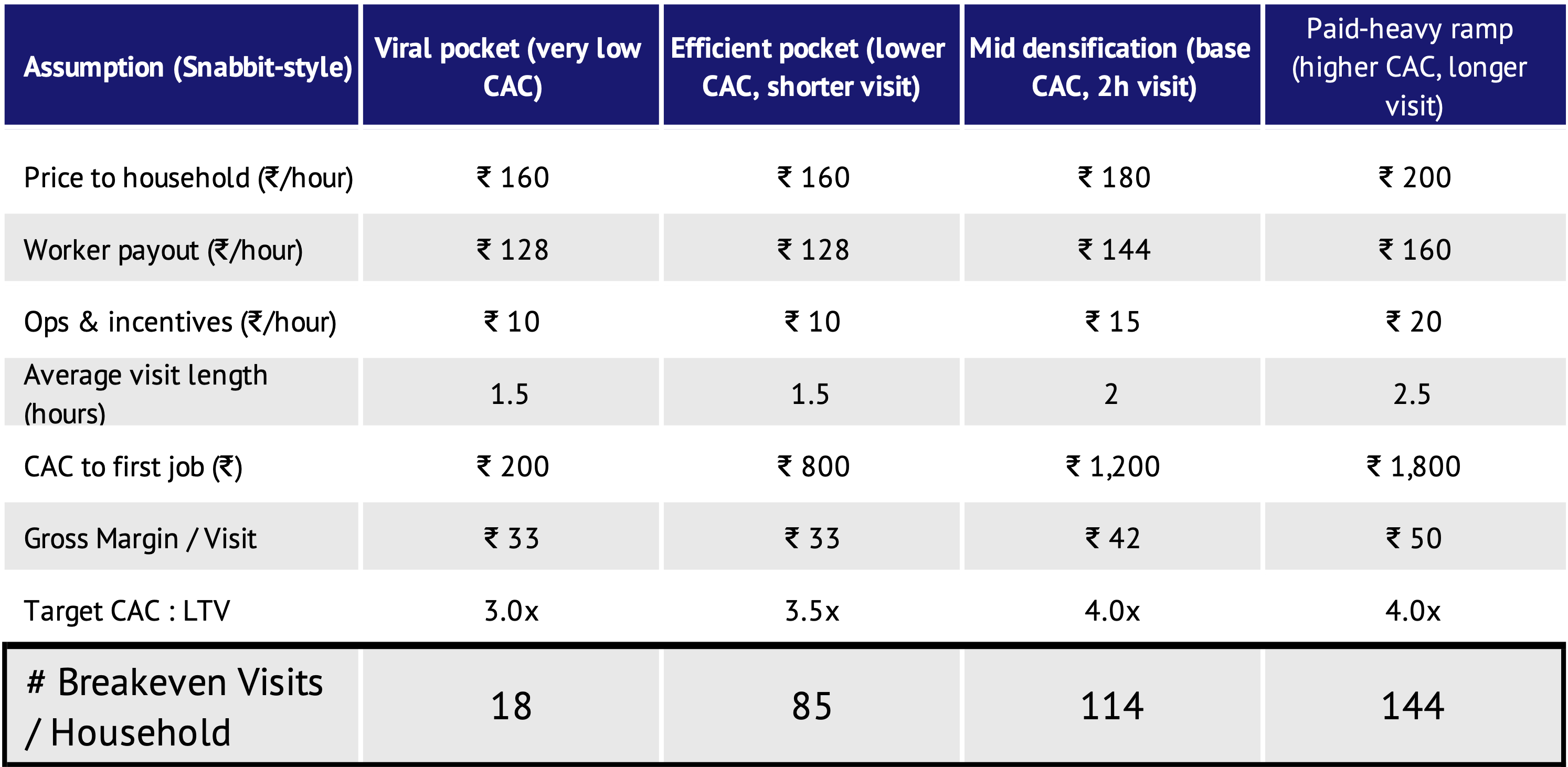

On-demand, per-booking models mostly trigger trials or cover gaps when a worker is absent. These can compound only if households move into recurring blocks — saved slots or weekly packs — or if other revenue lines help the math. Without that shift, customer acquisition costs stretch far ahead of what per-visit margins can recover.

Lead-gen or classifieds make sense when conversion from profile view to hire is steady and refund rates are low. The commercial focus is footprint and brand rather than repeat use, which limits compounding potential on its own.

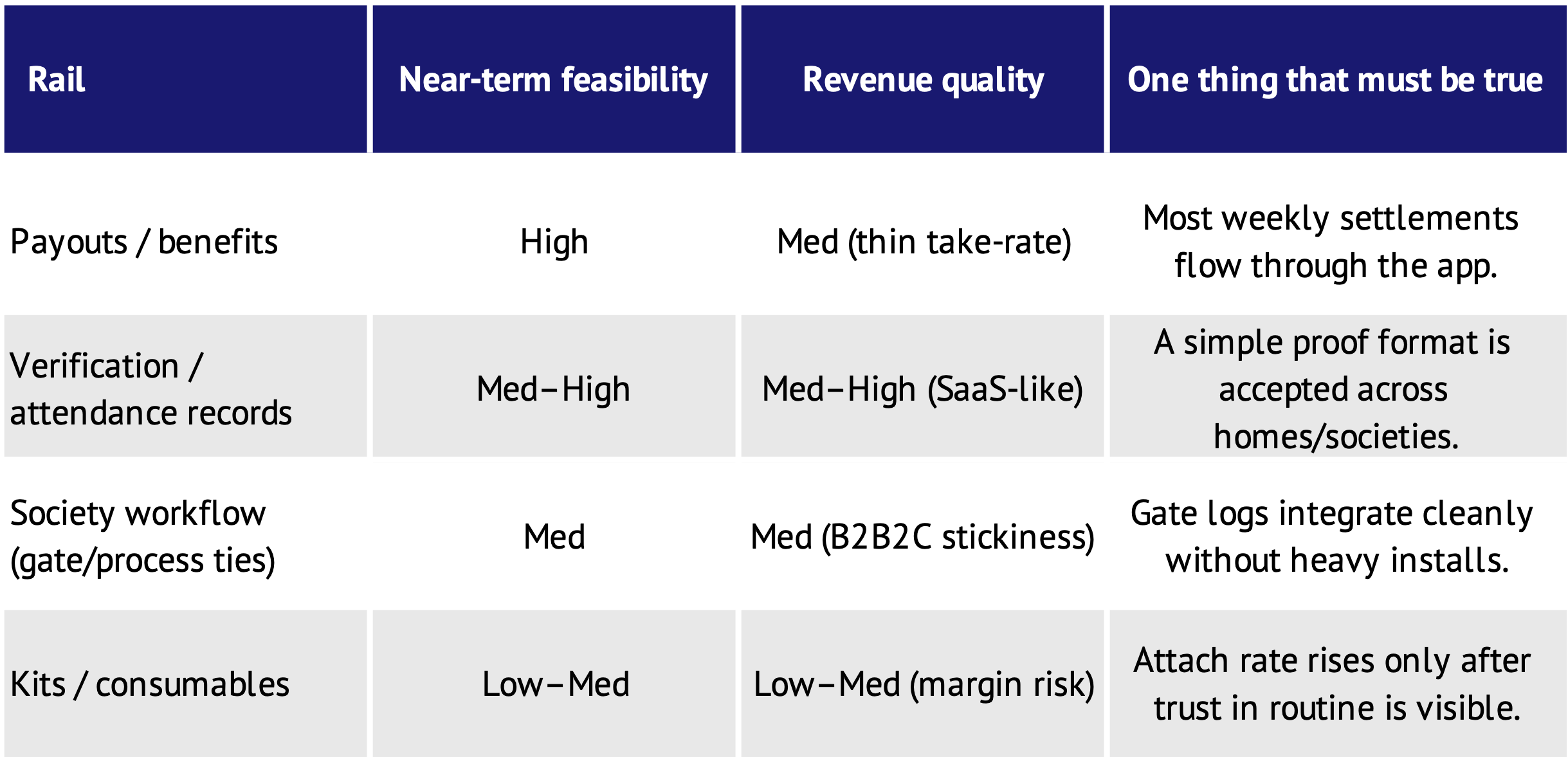

Rails models — payouts, verification records, society workflow, or kits — rely less on household fees and more on becoming the layer others depend on. These compound if a standard proof travels across homes or if most earnings reliably pass through the platform.

Those breakeven counts assume zero churn. If we apply ~36% reported retention for a per-booking model, even the “very low CAC” case moves from ~18 visits to roughly 50 visits to clear acquisition on an expected basis. At more typical CACs, payback stretches further. For episodic use, that’s a long road — which is why pure on-demand reads more like a façade: useful for trials and re-acquisition. The engine, if it shows up, is more likely underneath — in payouts, proof, and society workflow — or in tight pockets where routines hold on their own.

From the worker side, the picture is just as tight. At a payout of about ₹140 per hour, a worker needs around 140–150 paid hours a month to earn ₹20,000. That equates to about 4–5 hours of paid work a day — roughly 50% utilisation. Pushing higher would require very short commutes and highly reliable scheduling around peak hours, which is difficult in practice.

Where the Domestic Help Model Strains in Practice

Even when discovery works, the routine can slip off software. Trust does not always travel: a worker verified for one building may still face rechecks at another, and formats at the gate differ by society. When proof needs local rework, coordination tends to move back to calls and chats.

Time compresses into the same windows. Most households want morning or early evening slots, so small delays cascade. Visit lengths also vary — quick tasks in some homes, multi-hour blocks in others — which makes tight routing difficult. As load rises, on-time arrivals can wobble without adding incentives, and margins feel it.

Supply looks steady at the city level but fragile within micro-pools. A few missed days or a festival week can thin availability in one cluster while leaving others fine. Replacement speed becomes the product, yet the ops needed to deliver that speed can raise cost per visit.

Payments need a hook to stay on-platform. Once a match settles, many households prefer direct transfers or cash unless the platform is tied to something useful — simple records, on-time settlements, or a small benefit workers want. Without a reason to keep payouts flowing through the app, the fee line weakens quickly.

Read together, these frictions suggest the consumer surface can acquire and even re-acquire, but compounding likely needs more than discovery. That sets up the next question: if the fee line looks thin today, what are investors actually underwriting — a consumer engine that firms up locally, or rails where value accrues beneath the surface?

Two Paths VCs Might Be Underwriting

“Our tilt is simple: the consumer surface may test demand, but value likely accrues in rails unless routines hold locally without heavy ops.”

If the fee line from households feels thin, why do some investors still back domestic help platforms? Two broad paths are visible.

Path A: Consumer surface as the engine.

This is the more familiar bet. The idea is that routines in some dense pockets begin to hold — saved slots repeat, replacements arrive quickly, and simple records are tied to on-time payouts. If that happens, retention could rise without heavy incentives, CACs could fall, and the platform fee itself may start to compound. The marker to watch is whether 60–90 day repeats among first-time homes move up meaningfully on their own.

Path B: Value in the rails.

Here, the consumer layer is treated more as a façade — a way to acquire households and workers — while the durable revenue comes from rails beneath. Payouts and small benefits can add up if workers prefer the platform for settlements. Verification and simple attendance records could travel between homes or buildings. Society workflow, if tied to gate processes, may reduce friction across pairings. Kits and consumables can attach once trust is in place. Urban Company’s FY25 filings showed roughly a quarter of revenue from products, which suggests precedent for non-service lines.

Read this way, investors are not just underwriting discovery. They are either betting that routines begin to hold in enough pockets for the consumer engine to stand up, or that value will accrue in the underlying rails where proof, payouts, and workflow can travel.

Risks & Counter-Thesis

There are ways this can tilt against the reading so far. Routines could strengthen more than expected in a few dense pockets. If saved slots hold without incentives, replacements arrive quickly, and simple records stay on software, the consumer engine may start to stand on its own. In that world, a fee-led model could compound locally even if on-demand looks thin elsewhere.

A larger platform could also bundle the rails. If payouts, small benefits, and verification get packaged inside a widely used app — or tied to society gate processes in a uniform way — standalone rails would feel interchangeable. Convergence at the gate is a similar risk: if entry logs and formats standardise across buildings, parts of the coordination layer may shift inside incumbent workflows.

Fee resistance is another pressure point. Once a match settles, many households and workers prefer direct transfers unless the product is tied to something they value every week. If those hooks are weak, platform take-rates face pushback. Worker multi-homing adds to this: with multiple apps and informal networks available, supply can move quickly, making micro-pools fragile just when reliability matters most.

Read with caution, these pushbacks do not erase the opportunity in domestic help digitisation. They suggest the compounding case is narrow — either where routines hold without heavy ops, or where proof and payouts travel in a way a bigger bundle cannot easily replace.

You used my exact word s – I don’t know if that match weith the rest of the draft or not. Also we are not going to have these metric so don’t talk about that

Conclusion — Where Domestic Help Digitisation Likely Compounds

On the evidence above, this is not an easy consumer-tech scale story. Domestic help repeats by default, but keeping the routine on software — without incentives, week after week — is the real bar. On-demand looks like a façade that acquires; the engine, if it compounds, likely sits in rails.

The recent top-tier bet on Snabbit reads less like faith in per-booking margins and more like a frequency →rails thesis: use higher utilisation to route payouts and simple proof through the platform. That path can work, but it is ops-heavy and will scale by dense micro-pockets, not broad city averages.

Our stance is explicit: we’re rails-first unless clear local routines hold without heavy ops. Back the consumer surface only where saved slots repeat on their own, replacements arrive quickly, and most settlements and attendance records default to the platform. Until those markers are visible, treat the surface as acquisition — and build for where value actually travels.

We have also published our thoughts on several other spaces:

- Indian edtech: crowded edges, narrow middle—is it venture-fundable?

- Fast Fashion Q-Commerce: What Founders Are Testing — and Investors Are Missing

- Enterprise AI: The Pipes Are Taken. But the System Still Needs an Architect

- ESG SaaS in India: It’s Not the Trees — It’s the Revenue That’ll Drive Adoption