Why Fast Fashion Q-Commerce Deserves a Second Look

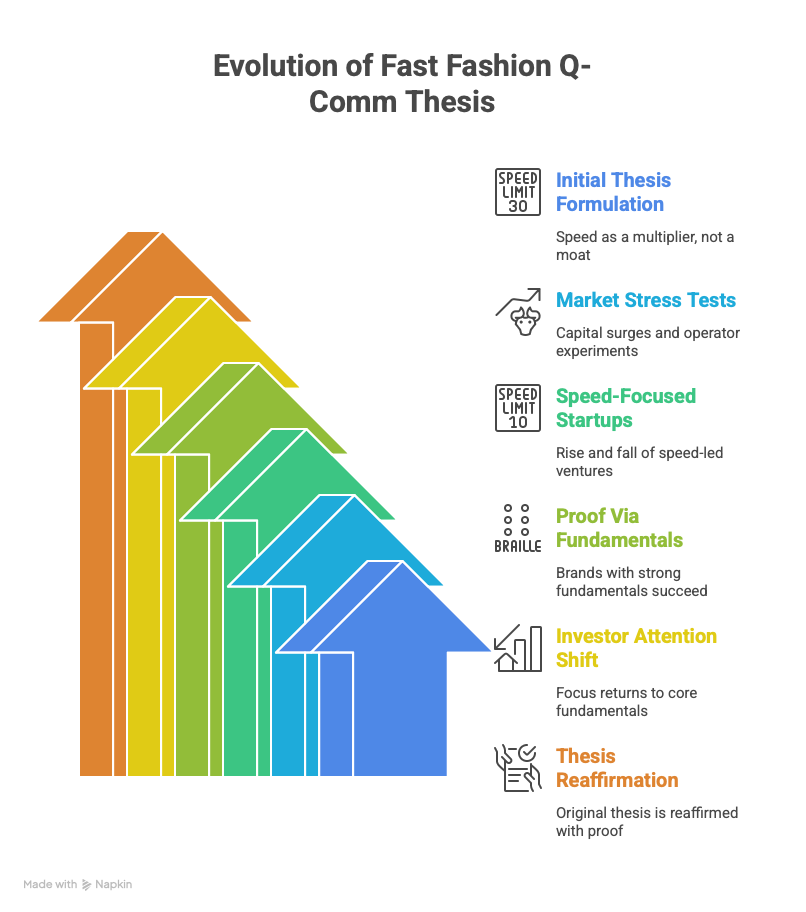

Earlier this year, we published a thesis on Q-commerce asking whether fast delivery could create a real moat — or if it simply made good businesses grow faster. Using fast fashion as the lens, we argued that speed doesn’t fix the category’s core problems: high return rates, thin margins, and inconsistent repeat. In that version of the market, Q-commerce looked more like a burn amplifier than a growth engine.

But things have shifted. Since February, several fashion startups — including NEWME, Slikk, and KNOT — have raised capital, launched 60-minute delivery pilots, and started investing in last-mile infrastructure. These moves weren’t just marketing noise. They reflected a deeper operational change: fast delivery is no longer just a narrative — it’s becoming a real part of how some of these brands function.

This blog revisits our original view in light of those developments. It’s not just a trend check. It’s a chance to test whether Q-commerce in fashion still behaves like a funnel tool — or whether it’s starting to reshape the fundamentals in a more durable way.

What’s Really Playing Out on the Ground

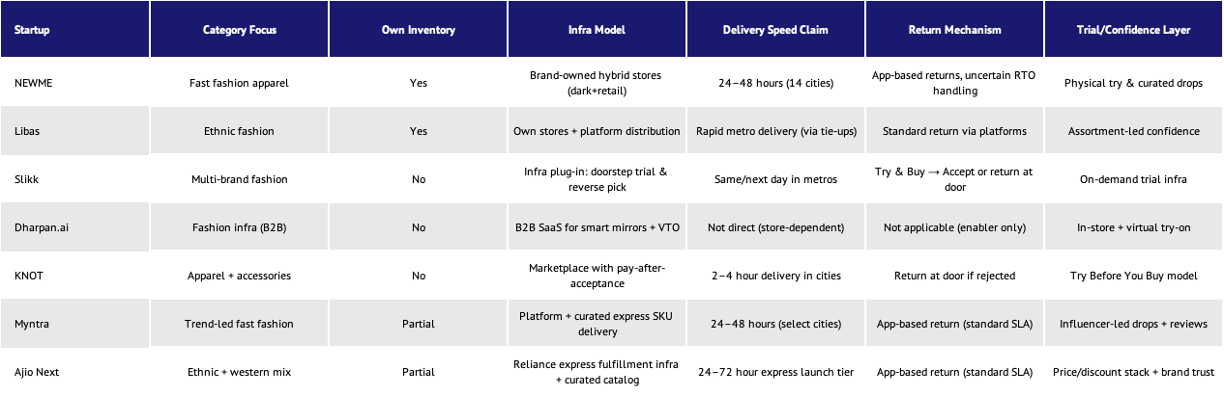

NEWME now runs 14 hybrid stores that double up as both retail touchpoints and local fulfillment hubs. These locations allow the brand to offer 60–90 minute delivery in key metros, with over 60% of orders reportedly routed through Q-comm platforms like Blinkit and Zepto. But the model isn’t wide or chaotic — it’s tight. Most of NEWME’s sales come from a small set of fast-moving SKUs, refreshed weekly. Speed here isn’t compensating for weak merchandising — it’s layered on top of what already works.

Slikk takes a different route. It uses a “Try Before You Buy” flow, where users can reject or accept items at the doorstep. Refunds are processed instantly. This isn’t about eliminating returns; it’s about building trust and reducing friction at the trial stage. The bet is that if users feel in control, they’re more likely to engage — and repeat.

KNOT, which pivoted from a social discovery app, now runs a marketplace with 60-minute delivery but no inventory ownership. It pays brands only after successful trial and delivery, passing both return and margin risk downstream. The model is lean, but the economics are still early.

Even incumbents are stepping in. Myntra’s M Now and Ajio’s Rush now offer deliveries between 30 minutes to 4 hours, using partner stores and dark hubs. These are not PR stunts — they’re pilots with growing coverage in cities like Bengaluru, Mumbai, and Delhi-NCR.

Across these examples, the shift is clear: fast delivery in fashion is being operationalized. It’s no longer a pitch deck concept — it’s on the ground, tied to real infrastructure and active order volume. The economics vary, but the shared goal is compression: shorten the time between discovery and ownership, and see if that unlocks habit.

Three Paths, Three Trade-offs

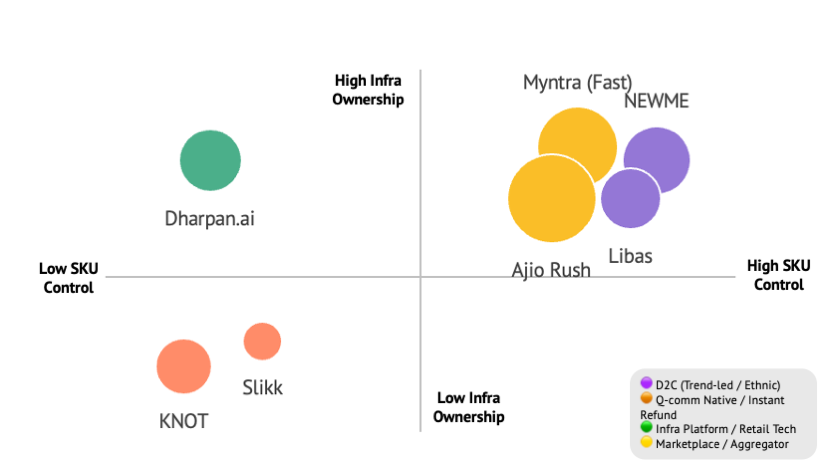

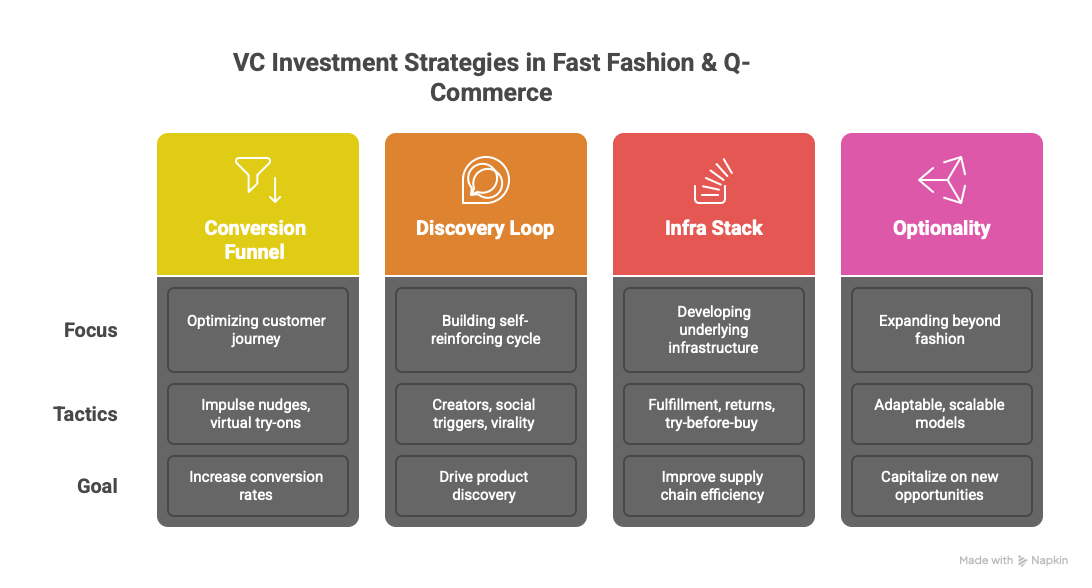

Fast delivery in fashion isn’t following a single playbook. Instead, we’re seeing three distinct models take shape — each choosing a different trade-off between control, capital, and speed.

The first is the brand-owned model, seen in startups like NEWME and Libas. Here, the brand controls everything — from product to discovery to fulfillment. Speed is enabled through storefronts that double as dark stores, allowing quick delivery without relying on external networks. But this model only works because the fundamentals are already tight: concentrated SKUs, weekly drops, and existing demand. Fast delivery reduces friction — it doesn’t create demand. The risk? Heavy capex and the challenge of scaling infra density city by city.

The second is the infra-layer model. This includes players like Dharpan.ai and refund orchestration layers used by Slikk. These aren’t brands; they’re enablers. Their bet is that brands will need tools to compress trial windows and reduce friction: smart mirrors, doorstep try-ons, fast refunds. The upside is low inventory exposure and multi-brand applicability. But defensibility is tough — these tools can become features, not platforms, unless deeply integrated into the brand’s stack.

The third is the marketplace overlay, where the startup doesn’t hold inventory or manage fulfillment — it simply connects demand to supply, like KNOT. The upside is speed and capital efficiency. The downside is fragility. There’s no control over SKU stacking, product fit, or return risk. If returns spike or AOVs drop, the model breaks. Deferred payouts don’t make the business defensible — they just postpone exposure.

Each model reflects a different answer to the same question: can Q-commerce in fashion work without rewriting fundamentals? The early evidence says it might — but only if the trade-offs are chosen deliberately.

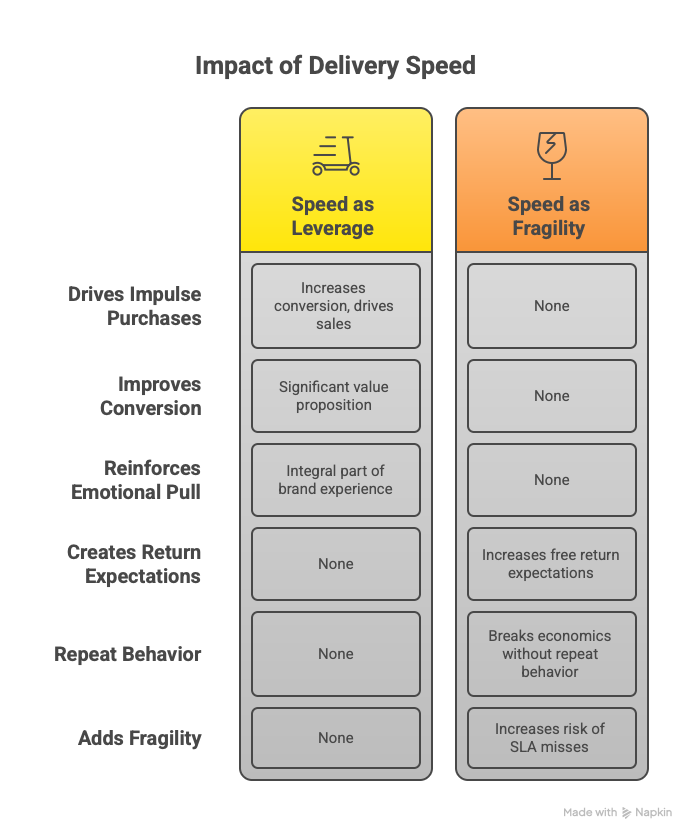

Fast Feels Like Progress — Until It Doesn’t

Speed gives early-stage fashion brands something that looks like traction. Faster delivery compresses feedback loops — founders see trial rates, return patterns, and repeat behavior play out in days, not weeks. For investors, this creates signal: orders are moving, customers are reacting, and products are being tested at velocity.

But that signal only matters if the fundamentals are strong. A brand with uncertain fit, weak stacking, or poor retention won’t magically improve because delivery is faster. Speed just reveals the cracks sooner. Faster delivery doesn’t fix returns — it accelerates them. It doesn’t improve retention — it makes weak repeat loops obvious.

This is where some of the investor optimism may be misplaced. There’s growing belief that Q-commerce helps “compress the funnel” — a phrase we’ve seen in several fund notes. In practice, compression without control is dangerous. For brands that don’t own their SKUs or hold inventory, like KNOT, fast delivery introduces volatility. If just a fraction of orders are returned, the already-thin margin pool disappears.

Some of this behavior is rational in the short term. If a fund is betting on founder speed or fast feedback, Q-comm GTM becomes a filter — a way to validate behavior loops early, even if the business model is still fragile. But that’s a narrow window. And it doesn’t mean the business is working — only that it’s being tested faster.

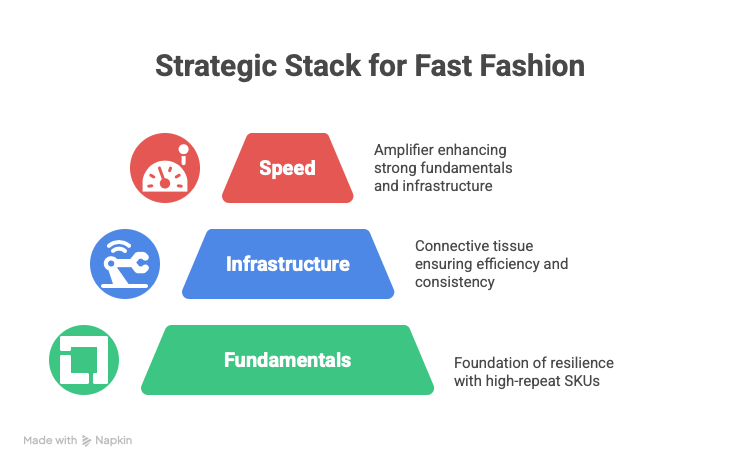

What’s Stayed True — And What’s Actually Moving

Our original take on fast fashion Q-commerce was blunt: speed doesn’t fix a broken model. If returns are high, AOVs are low, and repeat is weak — faster delivery won’t help. In fact, it may make things worse by adding pressure to refunds, compressing contribution margins, and exposing structural leaks earlier.

That still holds. But two shifts are now visible.

The first is in how speed is being operationalized. At the time of our earlier thesis, most fast delivery pilots were narrative-led. Today, we’re seeing real infra being deployed — from NEWME’s hybrid stores to Slikk’s doorstep trial flow. These aren’t margin-saving breakthroughs, but they show that speed can support conversion when SKU focus is tight and fulfillment is colocated. It’s a lever, not a fix — but it’s being pulled more seriously now.

The second shift is in capital behavior. Earlier, we saw Q-comm GTM as mostly investor signaling — a way to look “modern” without underlying durability. But it’s now clear that funds are using speed to validate product–market loops quickly. Especially in Gen Z–targeted fashion brands, speed is a CAC compression tool: drop, deliver, test, repeat. The economics may not be in place yet — but the learning velocity is.

So has our view changed? Slightly. Speed still isn’t a moat. But in certain contexts — with tight merchandising, colocated infra, and Gen Z urgency — it can function as a temporary growth layer. What’s different now is the intent: founders are building for it, and capital is underwriting that effort even before long-term margins are proven.

Not Every Problem Needs a Startup

One of the common instincts in fast-moving categories is to find tooling gaps and turn them into companies. In fashion Q-commerce, this has led to startup ideas around return orchestration, refund APIs, trial-layer middleware, and last-mile plug-ins.

But many of these problems aren’t fixable through tools — because they’re not tooling problems to begin with.

Fashion has high returns not because refund tech is broken, but because sizing, fit, and personal preference are subjective and variable. Delivery cost recovery fails not because the infra is missing, but because AOVs are low, repeat is erratic, and the margins don’t stack. These are structural issues. Adding an API on top won’t change that.

We explored whether there was room for a defensible layer between brands, delivery platforms, and customers. But unless that layer controls SKU velocity, fulfillment infra, or product merchandising — it’s just a convenience bandage. In most cases, the startup becomes a feature, not a platform. It doesn’t own enough margin to matter.

This doesn’t mean fast fashion Q-comm isn’t investable. It just means the value lies in full-stack execution or infra that’s bundled directly into the brand’s funnel. The real bets aren’t in middleware. They’re in models where speed is one part of a tightly built system — not a standalone promise.

What’s Actually Worth Backing

After three months of tracking Q-comm moves in fashion, our core view holds: speed works only when built on top of real fundamentals. But that doesn’t mean everything trying to move fast is flawed — it just means we need to be sharper in how we evaluate what’s working, what’s noise, and what deserves capital.

What’s worth backing is full-stack execution — where speed is embedded into the product and fulfillment loop, not just bolted on. NEWME’s hybrid retail–fulfillment model shows that when merchandising is tight and infra is colocated, speed can reduce friction and improve conversion. These models don’t win because of Q-comm. They win despite it — and then use it to go faster.

We’re also seeing signs that infra-layer tools can work — but only when bundled into a brand’s funnel and measured on actual usage, not just demos or pilots. Smart mirrors, doorstep trials, and refund automation help only if they lift conversion, reduce RTO, or drive repeat. If not, they risk becoming features chasing integration, not businesses capturing value.

And then there’s what not to back. Startups like Blip — which recently shut down — remind us what happens when signal outpaces fundamentals. Blip tried to marry fast delivery with influencer-driven drops and a community-led discovery loop. But returns were high, AOVs were low, and merchandising lacked coherence. Speed became a spotlight — not a moat. And without defensibility, the model burned too fast to fix.

That’s the core filter now: does speed sit on top of something that already works? Or is it compensating for something that doesn’t?

For founders, the message is clear: Q-comm can’t create product–market fit — but it can reveal it. For investors, the right bet isn’t on velocity — it’s on the systems that make velocity sustainable.

Like This Analysis?

We publish thesis-driven insights on markets where narrative clarity often lags signal. Read more from this series:

Why Agentic AI Changes the Game for GenAI BI Plays

ESG SaaS in India: It’s Not the Trees — It’s the Revenue That’ll Drive Adoption

Fast Fashion x Q-Commerce: Why Speed Isn’t Strategy

Ayurveda White Space: Everyone Believes in Ayurveda. So Why Is the Mass Market Still Unsolved?

LegalTech: The Courtroom Comes Too Late — Infra Starts Earlier

Building in a Complex Market?

We work closely with early-stage founders navigating regulatory grey zones, multi-tool workflows, and infra-heavy sectors. If this thesis resonates, let’s connect.