Why Q-Commerce Took Off — and What It Actually Tells Us

Q-commerce is no longer a novelty — it’s infrastructure.

In India’s top metros, sub-30-minute delivery has moved from hype to hygiene. Platforms like Blinkit, Zepto, and Instamart have normalized speed across grocery, grooming, and OTC health. And now, new brands are asking: should we go Q-commerce too?

The infrastructure says yes. But the economics often say no.

That’s because speed is no longer a differentiator. It’s a filter — one that exposes how ready your business model really is.

In the last 24 months, almost every consumer category has seen some form of Q-comm experimentation. But speed only creates leverage when layered on top of a product that already retains, repeats, and earns margin. Everywhere else, it simply accelerates cost.

As infra availability increases, so does the risk of misreading what Q-comm actually does. Founders and investors need to ask:

Does this product benefit from speed — or just tolerate it?

What Speed Actually Solves — and What It Doesn’t

Speed isn’t a growth engine — it’s a force multiplier.

Q-commerce is often framed as a competitive moat. But in our view, it’s better understood as a performance enhancer. When layered on top of the right product, speed removes friction and improves customer experience. But when applied to a business with weak fundamentals — low margin, poor repeat, high return risk — speed only magnifies the cracks.

This is a critical distinction for both founders and investors evaluating the Q-comm thesis.

Speed doesn’t create demand — it compresses it

Q-commerce works best in categories where demand already exists and the consumer simply needs less time to act on it. Use cases like restocking everyday essentials or last-minute grooming purchases fall in this category. Here, speed helps the consumer complete an already intended transaction — and in doing so, improves conversion and retention.

However, in categories where demand is infrequent or needs education, faster delivery rarely improves outcomes. High-AOV wellness kits, niche cosmetics, and apparel are all examples of products where the buying journey involves consideration, not urgency. In those cases, speed does little more than reduce the time between CAC spend and a refund request.

The Ola EV example: Speed as a UX feature — not a purchase trigger

Ola Electric’s recent rollout of 30-minute doorstep EV delivery is a good example of what Q-comm can and cannot do. While operationally impressive, it doesn’t change the buyer’s decision-making process. Consumers don’t choose a vehicle based on how quickly it shows up. They decide based on price, usage fit, brand trust, financing, and post-sale service.

In this case, speed enhances convenience but doesn’t influence the core purchasing trigger. The same logic applies across many product categories that have seen Q-commerce pilots — especially those with high-ticket sizes, low urgency, or non-repeatable use cases.

Speed is not a substitute for margin or habit

In our analysis, speed cannot offset structural weaknesses in a business. It doesn’t fix broken retention, improve contribution margin, or lower return rates. If the underlying product isn’t designed to repeat, stack, or deliver cash-efficient growth, Q-commerce will only accelerate cash burn.

This is why we see many vertical Q-comm models struggle despite early volume traction. Speed creates excitement — but not always economics.

The Five Structural Filters Every Q-Commerce Product Must Pass

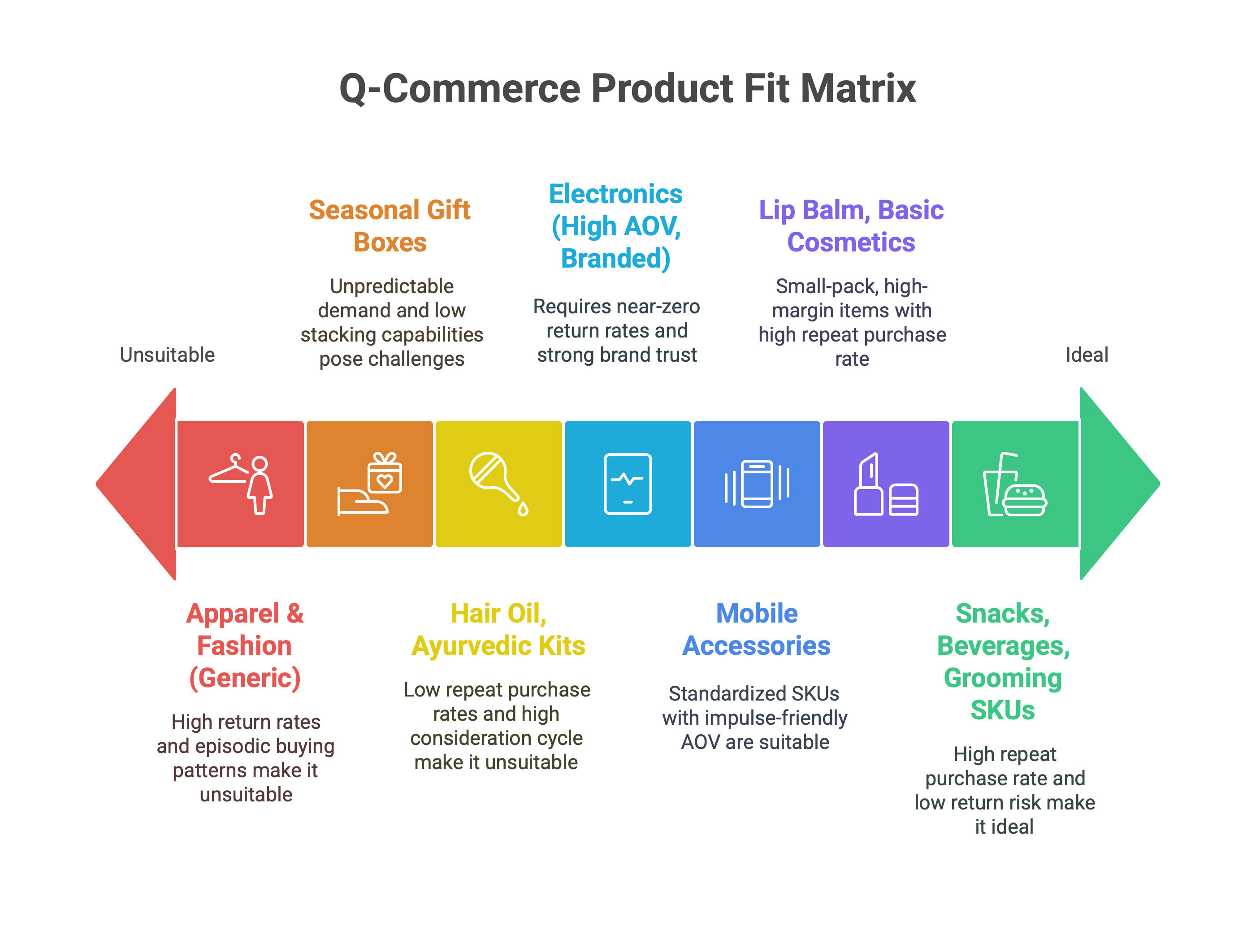

Just because a product can be delivered in 30 minutes doesn’t mean it should be.

As Q-commerce infrastructure matures, brands increasingly treat speed as a default distribution feature. But in our view, the real test is structural: does the product category actually benefit from speed?

To answer that, we’ve identified five critical filters that determine whether a product is truly Q-comm compatible. If a category fails more than two, the model likely breaks on contribution margin, retention, or operating complexity.

- Urgency of Use Case Speed adds value only when the product solves an immediate or time-sensitive problem. In categories like OTC health or personal care restocks, consumers benefit directly from reduced delivery time. But in fashion or herbal wellness, the urgency is low — and speed becomes irrelevant.

- Purchase Frequency Q-commerce delivery is expensive, and CAC remains high on most platforms. To justify the economics, a product must repeat often enough to recover acquisition cost across multiple cycles. Products bought once every 30–45 days — like hair oil or most apparel — rarely qualify

- Return and Replacement Risk High return rates introduce operational drag that Q-comm can’t absorb. Categories like fashion often see 30–40% return rates driven by fit and quality mismatches. Reverse logistics, refunds, and markdown losses compress contribution, especially when speed magnifies customer expectations.

- AOV vs Delivery Cost Recovery Most Q-comm deliveries cost ₹40–₹60/order in Tier 1 cities. Unless either AOV is high or product-level margins are strong, the unit breaks. Categories with small-ticket SKUs or low stacking potential (e.g., a ₹150 face cream with 30% margin) cannot absorb this cost.

- Delivery Suitability Physical form factor matters. Small, sealed, and sturdy items (like lip balm or trimmers) are ideal. Fragile, bulky, or temperature-sensitive SKUs introduce complexity — and often require a level of handling that’s misaligned with Q-comm infrastructure.

A Product Doesn’t Need All Five — But It Needs the Right Three

In our analysis, brands that pass at least three filters — ideally urgency, repeat, and either margin or operational simplicity — can justify Q-comm as a channel.

Failing on more than two often leads to negative contribution, even at moderate scale.

Fashion Fails the Q-Commerce Test — Structurally, Not Operationally

At first glance, fashion seems like a natural fit for Q-commerce.

High AOV, impulsive buyer behavior, and mobile-native consumers suggest strong compatibility. But in practice, fashion consistently underperforms on core Q-comm metrics — especially when evaluated in the aggregator model, where margins are already thin.

In our view, fashion fails to clear at least three of the five structural filters: low purchase frequency, high return risk, and poor margin stacking in single-SKU orders. These factors don’t just challenge scale — they challenge viability.

The Aggregator Model: What We’re Actually Testing

This model assumes the aggregator:

- Facilitates demand and last-mile delivery, but doesn’t own inventory

- Earns 10–20% of return-adjusted GMV as revenue from brands

- Bears the full cost of delivery (including reverse pickup, if applicable)

- Operates in a context where platforms do not yet offer customer-facing returns, though that may evolve

Even if platforms like Zepto or Instamart introduce reverse logistics in the future, the core dynamics — high returns, low repeat, fragile margins — remain unchanged.

Walkthrough Example: ₹800 AOV, 10% Return Rate, 70% Resale Recovery

Let’s say a fashion item is sold at ₹800.

If 10% of orders are returned and 70% of those are successfully resold, the aggregator loses ₹24 in GMV. That leaves an effective GMV of ₹776.

With a 15% commission, the aggregator earns ₹116.

Assuming a delivery and potential reverse logistics cost of ₹50, the margin before CAC and platform costs is ₹66.

This margin erodes quickly as return rates rise or resale recovery drops.

Fashion Q-Comm Margin Sensitivity (Aggregator Model)

Speed Doesn’t Solve the Real Problem

Fashion’s core friction isn’t logistical — it’s structural.

High return rates lead to margin loss, low repeat behavior limits CAC recovery, and single-SKU baskets struggle to scale. Speed cannot compensate for these issues; it simply accelerates the exposure.

Even if platforms enable returns or drive down delivery cost, fashion’s fundamental weaknesses in Q-comm remain. In our view, the model is structurally broken — not just operationally immature.

When Can Fashion Work in Q-Comm?

It can work — but only in tightly defined scenarios:

- High-margin private label SKUs

- Low-return categories like accessories or fashion basics

- Stacked baskets that dilute delivery cost

- Or models where acquisition is subsidized by organic discovery

Outside of these, fashion in Q-comm often delivers speed — but not sustainability.

Case References — What Pattern Recognition Tells Us

The Q-commerce story isn’t short on experiments — but very few have scaled.

Over the past five years, multiple verticals have been tested with some form of rapid delivery. What emerges isn’t just a mixed bag of results — it’s a clear pattern. The winners tend to be low-return, high-frequency, margin-rich categories. The rest end up subsidizing velocity.

Here are three cases that help anchor that pattern.

Case 1: Fynd — Fast Fashion with Speed, But No Structural Edge

Fynd began as a fast fashion discovery platform offering rapid delivery, particularly in urban areas. In 2019, it was acquired by Reliance Industries. At the time, it seemed like a strategic bet — combining Reliance’s scale with Fynd’s tech and inventory-linking capabilities.

But post-acquisition, the standalone model never scaled meaningfully. Despite infrastructure support, the same issues persisted: high return rates, low stacking in orders, and uneven repeat behavior. The platform struggled to deliver sustainable unit economics in a category that fails on key Q-comm filters.

The key learning: even with distribution muscle and logistics backing, fast fashion doesn’t work in Q-comm unless return risk, margin, and frequency are fundamentally reengineered.

Case 2: Nykaa’s Targeted Q-Comm Experiments

Nykaa has selectively deployed 30–60 minute delivery in urban zones for high-frequency SKUs — lip balms, small cosmetics, grooming tools. But the bulk of its business still comes from standard delivery. This reflects clear internal calibration: speed is useful, but not universally necessary.

Speed is a channel layer — not the core proposition. That distinction has been central to Nykaa’s category-specific experimentation.

Case 3: Platforms Testing Electronics

Q-commerce platforms have offered electronics like earphones, firesticks, and grooming kits. These products worked because they were standardized, durable, and had near-zero return rates. But even here, the model only holds if AOV justifies the delivery cost, and returns stay below ~2%.

What’s clear: it’s not about the category label — it’s about structural fit at the SKU level.

The Meta-Learning: Speed Doesn’t Rescue Weak PMF

Our view is that Q-commerce is best used to stress-test a product’s readiness — not manufacture artificial growth. If the product already works — strong retention, margin, and habit — speed helps you scale faster. If it doesn’t, Q-comm simply accelerates losses.

Most failed experiments weren’t logistics failures.

They were category misreads.

For Founders and Investors — How to Evaluate Q-Comm Fit

Q-commerce is seductive — but unforgiving.

The infrastructure is available. The demand spikes look exciting. And the investor pitch is easy to frame. But speed adds cost — and exposes weak fundamentals quickly. Founders and investors need a sharper lens to evaluate when Q-comm is an asset versus when it’s a liability.

Here’s how we recommend pressure-testing a product’s Q-comm readiness:

- Would the customer still buy this product if it took 2 days? If the answer is yes — and nothing about the use case changes — speed likely won’t improve conversion. You’re just compressing the same journey.

- Is this product bought often enough to amortize CAC? If repeat is quarterly or lower, and retention isn’t habit-driven, Q-comm will make CAC recovery harder — not easier.

- What’s the real cost of a failed delivery? In high-return categories like fashion or cosmetics, one failed delivery can wipe out contribution from multiple successful ones. This is especially relevant in aggregator models where margins are thin.

- How many SKUs are bought per transaction? Single-item orders rarely make Q-comm work — unless margin is unusually high. Stacked baskets or bundled SKUs improve contribution per delivery.

- If speed disappeared tomorrow — would the product still grow? Speed should accelerate growth — not manufacture it. If removing speed kills traction, the core product isn’t ready.

In our view, Q-commerce should be treated as a channel filter, not a business model.

It can amplify an already working engine. But it won’t fix one that isn’t firing.

Final Take: Q-Commerce Is a Filter, Not a Framework

Q-commerce is no longer an edge — it’s a test. When the fundamentals work, speed enhances them. When they don’t, speed accelerates exposure. The most successful use cases aren’t built because of Q-comm, but in spite of it — grounded in margin, retention, and structural fit.

As infrastructure becomes ubiquitous, the opportunity isn’t in chasing speed. It’s in using it to validate whether the business can scale sustainably — with or without the 30-minute promise.

At Accrezeo, we publish data-backed insights to help founders and investors stress-test categories, evaluate timing, and sharpen conviction. If you’re building in Q-commerce–relevant verticals or preparing to fundraise, this kind of structured analysis can strengthen both strategy and visibility.

We’ve recently published similar deep dives on:

If you’re operating in or adjacent to these spaces and want to develop a thesis-led narrative — or know someone who would benefit from this piece — we’d be glad if you passed it along.